December 30, 2006

December 29, 2006

help desk

sigh

So, sailing far, far off-topic for D'Ed Reckoning, I'm posting a Help Desk query here.

Does anyone have - or can anyone quickly produce - a sound, illustrative definition of the expressions "money is fungible" and/or "opportunity costs"?

I think some of you have been following the Fields drama here in Irvington: the $4.8 million dollar bond being floated to improve the fields, install artificial turf, build 4 tennis courts, put up stadium lights, etc. This on top of $55 million indebtedness assumed over the past 7 or 8 years.

The bond failed.

The pro-bond forces included the school board, the administration, the high school principal, and the teacher's union.

The high school principal was so pro-bond that he gave the name of the parent who was "heading the committee to defeat the bond" to the union.

The union head called the parent at home to tell her the teachers had voted and they supported the bond.

That parent wasn't heading the committee to defeat the bond, though it was certainly no business of the union's one way or the other if she was.

But she wasn't. No one was heading the committee to defeat the bond because there was no committee. There was no organized opposition at all.

In town the pro-bond forces seemed to include everyone who was anyone, all the machers, big and small.

A group calling itself "Team Irvington" (I'm Chevy Chase and you're not!) put up 800 "Support Our Students Vote Yes" signs all over town one day and paid for zillions of ads featuring large photos of field-less teens staring glumly into the camera. The high school principal signed on with Team Irvington and put his name on all the Team ads along with 20 or 30 or 40 other Prominent Citizens. He wrote his own letter to the editor supporting the bond, and included a pro-bond statement in his MESSAGE FROM THE PRINCIPAL, which arrived in the mail bundled with students' interim grade reports.

Meanwhile the anti-bond people were walking around with bags over their heads.

In a tiny little town like this, the sheer size and force of the pro-bond contingent was unnerving. After Team Irvington's "Support Our Students" signs went up Ed said we had to put up signs, too. I was by then so intimidated I felt too scared to put up signs even after dark, or maybe especially after dark. Even taking Surfer with me I was still scared. I ended up punting.

The next day Ed made even more signs and spent two hours late that night posting them.

Suddenly everyone else started putting up "No" signs under cover of dark, each with a different message. You'd wake up in the morning and: new signs! This went on for days; the townspeople of Irvington had created a Sign Lollapalooza.

My favorite sign was Education not remediation.

I'd love to know who put that one up.

Ed and I counted at least 6 different "No" signs altogether. We don't know who put them up, though we did discover the identity of the mom who wasn't heading the committee to defeat the bond. She put signs up in broad daylight and was followed by two teens in a car. ("Team Irvington" had a huge crew of teenagers working with them.)

After Ed put up signs, I put signs up, too. Naturally I decided to post mine at 10 in the morning just to show I wasn't scared to put up signs.

In retrospect, that was probably dumb.

On election day, the District Clerk laid out all of the Board's many "FAQ"s and "information sheets" on tables in front of the voting booths, next to which stood an easel displaying an architect's drawing of the beautiful plans for our beautiful new fields.

A parent who is an attorney came in to vote around 1 pm, spotted the pro-Bond material, and pointed out to the District Clerk that this was a violation of election law. The Clerk said voters had been coming in asking for information, so she'd put out information.

Word of the Clerk's intervention made the rounds sometime after dark, and at that point Ed and I both figured: debacle.

At 9:30, when the email from the Board saying the bond had been defeated arrived, I couldn't process the numbers. I kept staring at them thinking, "Those numbers look like the bond lost, but that can't be." I had to read the words below the numbers ("The referendum does not pass") to get it. A friend told me she couldn't even process the text, and had to re-read several times before it sank in.

The turn-out was huge, possibly the largest turn-out in recent history.

Final vote:

No: 845

Yes: 798

++++++++

The immediate concern, post-vote, is that we still need fields. (One of the oddities of the vote was that no one publicly or even privately disputed the core issue, which is the need for capital improvements to athletic facilities which haven't been maintained in years and are suffering from over-use to boot.)

The good thing is that a lot of people will be talking back and forth, figuring out what needs to happen to swing 25 no votes to yes.

Whether the fairly large contingent of parents who were posting signs like Education not remediation can begin to make their message heard is another question.

Which brings me to the help desk.

Tonight's Rivertowns Enterprise quotes both the superintendent and the high school principal saying that voters "didn't understand" the bond.

What we didn't understand was that the bond would have no impact on academics. The bond was separate. It was a bond. You can only use a bond for capitol improvements, not for academics, so, ergo, another $4.8 million in debt will have no effect, none, on academics.

This is quite disheartening.

Parents and residents - lots of parents and residents, not just the usual suspects - spent weeks in the run-up to the election asking the board to address the question of opportunity costs & trade-offs. This question was asked repeatedly, and was not-answered repeatedly. The Board put out FAQ after FAQ after FAQ, not one of which addressed opportunity costs and trade-offs.

Apparently the District plans to carry on not addressing the question. It worked so well in the election, after all.

So I'm disheartened.

I was allowing myself to believe that the District would be humbled by this defeat, which was a bad one any way you slice it. They had everything going for them. They dominated all communication; they sent home one pro-bond communication after another while refusing to give equal time to anti-bond arguments (I asked); they sicced the union on parents; they violated election law.

And they still lost.

Ed says that, historically speaking, it is extremely rare for a disorganized, spontaneous, grass-roots movement to prevail against an organized opponent. The vote may have been close, but the loss is large.

So I was thinking that the first words out of the District's mouth would not be "Parents are dumb."

Wrong again.

Ed is writing yet another letter to the editor attempting to explain trade-offs and the fungibility of money.

It's not easy.

I tried to find a simple account in my economics books, but so far no luck.

[update: Ed's letter is pretty good]

If you know a good account, or can write one yourself - or if you have "teaching examples" of money being fungible - I'd love to read.

Thanks!

December 27, 2006

Kitchen Table Math, the sequel

The site has been on its last legs for awhile now.

It finally collapsed a few weeks back. It's still readable, but no one can edit or comment, including me. Carolyn thinks the password file is corrupted.

It's time to launch Kitchen Table Math, The Sequel.

I've been thinking: this time around I'd like to start a group blog. Carolyn thinks it's a good idea.

In a group blog ktm regulars would be invited to join; you could put up posts on the front page whenever you liked.

As new readers came along we could, and no doubt would, invite them to join, too.

People could post as much or as little as they liked; a person could join and post nothing at all. Everyone can carry on commenting on posts in the normal fashion, too.

What do you think?

December 26, 2006

Reading Comprehension

We can summarize what we know from the last 25 years of research on reading comprehension strategies fairly concisely:

- Teaching children strategies is definitely a good idea.

- The evidence is best for strategies that have been most thoroughly studied; the evidence for the less-studied strategies is inconclusive (not negative) and, therefore, there is not evidence that one strategy is superior to another.

- Strategies are learned quickly, and continued instruction and practice does not yield further benefits.

- Strategy instruction is unlikely to help students before they are in the third or fourth grade.

Modern reading instruction is all about teaching reading comprehension strategies, even though these strategies are "learned quickly, and continued instruction and practice does not yield further benefits." Willingham says:

I don’t believe that students continue using these strategies into adulthood. Literate adults do not construct story maps as they read the morning paper, nor do they pose and answer questions for themselves. They do, however, understand that the goal of reading is to obtain meaning, and they monitor their own comprehension; that understanding is likely what remains with the tenth-grader who was taught a set of reading strategies in fourth grade.\

That's point three from the list above. Educators seem to stop reading after point two.

Point four is that the teaching of reading strategies shouldn't begin until after students have learned to decode fluently, i.e., after about the third grade.

Strategies require attention and space in working memory (e.g., Cain, Oakhill, and Bryant, 2004; Calvo and Castillo, 1998). Students who are still learning to decode fluently do not have enough working memory space available to implement strategies. Their working memory is occupied by decoding. A natural conclusion is that there is not much point in teaching reading strategies before students have gained that fluency—for most students, that will be in the third or fourth grade.

I'll save my commentary on the wacky decoding instruction favored by educators for another post. Suffice it to say, educators believe that decoding is quest for meaning, not word identification, and, as a result, teach decoding like it's merely another reading strategy. It's not.

So what should effective reading instruction be about?

Teaching reading strategies is worthwhile, but we should bear in mind that knowledge of strategies is only a small part of what makes an effective reader. A good reader also decodes fluently, has a broad vocabulary, and has wide-ranging background knowledge.

Formal reading instruction should be about teaching decoding skills in the early grades then briefly teaching a few reading strategies. But that's not enough to make good comprehenders.

What's also needed is the development of a broad vocabulary and wide-ranging background knowledge -- two things that aren't getting done in most schools.

The need for a broad vocabulary should be self-evident. It’s hard to understand the meaning of a sentence if you don’t know the meaning of the constituent words. There are times when you can deduce the meaning of an unknown word from the context, but you need to understand most of the text to be able to puzzle out the meaning of the unknown word. Your ability to do so drops rapidly, however, as the number of unfamiliar words increases (Laufer, 1997).

Background knowledge also has profound effects on reading comprehension. Have another look at the three classes of strategies in the table—two of them rely on or are facilitated by background knowledge. Encouraging students to relate the text they are reading to background knowledge won’t help much if the students don’t have the relevant background knowledge. Less obvious is the fact that relating sentences to one another also often requires background knowledge.

My assessment of the state of reading instruction is that the decoding piece is frequently done poorly (this alone causes failure in many students) and the reading strategy piece is greatly overemphasized (and taught too early). The other two piece of the puzzle, vocabulary and background knowledge, are underemphasized as part of the growing trend to minimize the instruction of content knowledge in school.

You can't miss two of the four pieces of the puzzle and then be surprised when you fail to create good readers.

December 21, 2006

Today's Ethical Dilemma

I gave my freshmen a writing assignment to test how well they'd picked up on the elements that made up an epic. I knew they could recite the characteristics of an epic to me, but I wanted them to show me that they'd learned what makes an epic by writing one of their own. While I'd hoped they'd do well on this assignment, they've demonstrated their lack of writing abilities before, so I was nervous.

But what I got back was excellent.

The kids not only followed the guidelines of the assignment, demonstrating they understand the concept of what makes an epic, but they were also so creative. I'm in Panera right now grading, and I'm enjoying reading their assignments. They are riddled with grammatical errors, but they're so creative and entertaining, I've adjusted my rubric to make grammar less important.

Who thinks that Anon Teacher did the right thing?

This is what our current education system has wrought. Educators have adjusted their rubrics for teaching kids how to read, write, and do basic math so as not to require proficiency according to society's understanding. I'm certain that the grammatical errors made by these students are not of the esoteric or pedantic variety, but of the painfully embarrassing and brutally obvious variety.

It should not be a trade-off between creativity and proficiency in the use of the English language. You should be able to write simple sentences that are grammatically accurate by the ninth grade.

Being that the job prospects for aspiring epic writer is already small, I would think that the job prospects of the epic writer with poor grammar skills is virtually non-existent. I can assure you that colleges and future employers will not be adjusting their rubrics to let grammatical incompetence slide by.

I suppose NCLB is to blame for this as well.

Opportunity Costs

My idea of “discovery” is quite different than his. Take the problem of finding a formula for the sum of interior angles of a convex polygon which we discussed in class. The solution hinges on the fact that the sum of the angles of a triangle = 180 degrees. You could approach teaching this lesson by guided discovery, and show how to split up a quadrilateral and pentagon into triangles to derive the sum of the interior angles. After several minutes of discussion, some students may identify key patterns and the teacher could wrap it up. I suggested this to Mr. NCTM, remarking that it really wasn't giving away the store and there was still some discovery involved.He nodded acknowledgement but continued to “guide” our class to the constructivist approach: 45 minutes of discovery including having students actually measure the angles of various convex polygons with a protractor, and after accounting for error in measurement, making conjectures and seeing “patterns”. One fellow student asked why one would do that when in fact geometry was about deductive reasoning and learning to reach conclusions about measurement without the aid of actual measurement devices. Mr. NCTM said students should be given free reign to discover the superiority of the deductive method.

For fear of being forever branded as a blog poseur, I hesitate to say whether my approach would be called “direct instruction” or “guided discovery” or Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development and its related term, “scaffolding.” I just offer that the type of discovery my approach entails is what I and others in my age group had growing up. Given a choice between giving students 45 minutes to reach an “aha” experience, or 5 to 10 minutes, I and others like me opt for the latter.

The cost of "discovery learning" is instructional time.

Let's assume that the instructional goal is to convey a particular concept to the students. In Dewey's example the concept was that the sum of the angles of a triangle = 180 degrees. Let's further stipulate that this concept can be adequately conveyed to a student using either a discovery method or a direct instruction method and that in both methods the teacher will attempt to convey the concept with understanding.

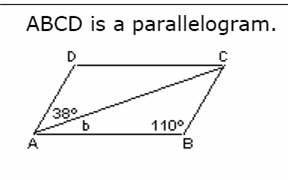

Whether the student has actually learned the concept and understands it is easily testable. For example, after the teacher has taught the sum of the angles of a triangle concept and the concept that alternate interior angles of two parallel lines are congruent, the student who understands both concepts should be able to solve for b in the following problem:

Students who can't solve the problem likely do not understand either or both of the taught concepts. In fact, there is a good argument that the concepts have not been "taught" to these students since they have not yet learned the concepts. The effective teacher will go back and reteach the concepts until the students understand them.

Students who can't solve the problem likely do not understand either or both of the taught concepts. In fact, there is a good argument that the concepts have not been "taught" to these students since they have not yet learned the concepts. The effective teacher will go back and reteach the concepts until the students understand them.The initial learning of the concept is only the first half of the learning process. The second part is retaining the concept in long term memory. This is most efficiently achieved by the student overlearning the concept through practice. Retention is also easily tested by giving a delayed test, say at the end of the course, containing a problem similar to the one given above.

Now let's get back to Dewey's example so we can understand the hidden cost of discovery learning. The sum of the angles concept should be teachable in about 10 minutes of classroom time using either direct instruction alone or some combination of direct instruction and a few minutes of discovery opportunity, as Dewey suggests. In contrast, the guided discovery method, as it is typically practiced in problem-solving/constructivist curricula, might take four times that amount of classroom in order for all the students to discover the concept. In this same period of time, the direct instruction teacher could teach another concept and still have plenty of time left over for the students to practice the concepts they've previously been taught, thus improving their retention.

These are the opportunity costs associated with the discovery learning pedagogy. The opportunity to learn more quickly through more efficient forms of instruction and the opportunity to practice what you've already learned.

The counterargument you most often hear from discovery learning proponents is that students understand the material better if they construct the knowledge for themselves. This might be a legitimate argument if it were true, but so far it remains unproven. Kids who learn via discovery learning are not demonstrating their superior understanding in simple skills tests like the example I've given or, for that matter, in any demonstration or test that supposedly tests higher order thinking skills, whatever they might be.

December 20, 2006

Giggles induced

We are not calling for an end to ESEA and to suggest otherwise is to engage in a lie. We want all of NCLB's provisions undone and a return to ESEA pre NCLB.

Since NCLB only added accountability measures, the Education Roundtable wants to go back to those halcyon days when the feds' role was to "slop the hogs" with money and educators would feed hungrily at the trough without anyone looking over their shoulder. That kids and taxpayers were the only special interests that weren't benefiting from such a system does not seem to bother the Education Roundtable.

Let's hit some of the more unintentionally hilarious points made in the petition. According to the Roundtable, NCLB needs to go because:

8. Reflects and perpetuates massive distrust of the skill and professionalism of educators.

I'm speechless. Let's say I go take my driver's test and fail the exam. Would other drivers have reason to distrust my driving skills?

12. Applies standards to discrete subjects rather than to larger goals such as insightful children, vibrant communities, and a healthy democracy.

Now those are standards that I'd like to see--state standards for evaluating when children are insightful, when communities are vibrant, and democracies are healthy. Hopefully, schools will teach to the test and devote the morning to teaching insightfulness and the afternoons to teaching vibrancy. Hopefully, they'll do a better job teaching these subjects than they did teaching math and reading.

10. Emphasizes minimum content standards rather than maximum development of human potential.

11. Neglects the teaching of higher order thinking skills which cannot be evaluated by machines.

Have you ever seen a person with higher order thinking skills who couldn't answer basic skills-type questions? No? Me neither. If anything, NCLB has shown that schools aren't doing a very good job imparting basic skills, let alone those elusive higher order thinking skills. Let's stick to baby steps.

5. Ignores the proven inadequacies, inefficiencies, and problems associated with centralized, "top-down" control.

Isn't that the existing problem? Public schools have always been run in a centralized, "top-down" manner.

1. Misdiagnoses the causes of poor educational development, blaming teachers and students for problems over which they have no control.

It may not be true that those that can't do, teach. But what is becoming increasingly obvious is that those that can't teach want to shift blame.

Funny Update One: The Rountablers are attacking in the comments and showing us that non sequiturs, logical fallacies, and blind adherence to ideology don't make for compelling arguments. You're being ridiculed in the edusphere and your saner liberal allies have hung you out to dry. Time to reevaluate your position. First rule of holes: when you're in one, stop digging. They do seem itching for a fight. Maybe Edspresso will host one of their week-long debates. You listening, Ryan?

Update Two: Once again I've profitted from heeding the advice of America's greatest president, Calvin Coolidge, who once said “If you see ten troubles coming down the road, you can be sure that nine will run into the ditch before they reach you.” In this case my inestimable band of frequent commenters have fought back the swarm of tinfoil-hat-wearing roundtablers much better than I could have.

Color me sceptical

I've found that most traditional textbooks oversimplify and isolate concepts, and yet, are still too difficult for non-readers to use. They don't generally push students to think, but offer repetitive, and boring, practice.

and

My primary goal as a teacher is to help my students understand the reasoning behind math rules and procedures. I have several core beliefs about this: (1) Understanding is constructed by the learner, not passively received from the teacher. (2) Understanding is built by making connections between as many strands of knowledge as possible. (3) Understanding is galvanized through communication. (4) Understanding is only valuable when you reflect on it and question it.

and

My sequence and pace are set by a long-term plan that I have designed to catch the students up on second-, third- and fourth-grade material as well as introduce every single D.C. public schools fifth-grade standard by testing time. I model my word problems after the eighth-grade text that I used in Louisiana because those problems require the level of understanding that I am looking for. I focus on non-traditional problems so that students are forced to think.

She even issues a less-effective kind of praise:

You're brilliant! I can't stand it.

One indication that things might be amiss is:

although Suben's students improved markedly on the nationally standardized test, that was not enough to meet the first-year federal target for No Child Left Behind when they took the new and unusually rigorous D.C. Comprehensive Assessment System test.

but, state tests are often so awful that they are not fair indicators of student knowledge. The D.C. test may be such a test.

I know performance gains of this magnitude in fifth grade math are possible in inner city schools. See the fifth grade performance (pdf) of the City Springs School in Baltimore. But, in one year? In City Springs in took the 2003 fifth grade cohort five years of good teaching to hit this level, using a curriculum that's been tested, retested and revised over the course of thirty years.

In any event, I am having trouble suspending disbelief when I hear things like this

What's the key. It's not that my lessons are so dramatically better than anyone else's lessons. It's just that we, the students and I, own our lessons.

No one who really knows how to teach math effectively says things like that. But, maybe it's just youth speaking. Or, maybe there's a massive disconnect between the rhetoric and the actual teaching.

December 19, 2006

Teaching Reading is hard work

Could you imagine a surgeon who only performed easy procedures, regardless of their efficacy, because he didn't want to put the work in necessary to perform the difficult procedures that were more effective? Could you also imagine this surgeon then labeling all the patients he failed to cure as "healing disabled" and referring them to another surgeon? Of course not.

I bring this up to preface an illuminating discussion I came across on the Direct Instruction listserv on the topic of Reading First schools with large "at risk" populations continuing to choose what they like as their core reading program rather than what works. Under Reading First, schools were often required to adopt an intervention program for the kids who inevitably failed to read using the school's core program. Let's see how the system works as explained by one administrator in the know:

In deciding which program to adopt as core, it would be wise to understand a school's student population. Is it "typical"? Or is it "at risk"?

Even though all Reading First Schools have a high percentage of at risk students, the decision at most of them has been to select Open Court or Houghton Mifflin because these programs are more familiar to decision makers, are far less demanding to teach to fidelity, and appear to have more literacy components, giving the impression that students would be able to engage in a wide range of comprehension activities sooner.

Decision makers are also aware of staff resistance to the direct instruction teaching demands of Reading Mastery, even though they may also be cognizant that research studies and recognized experts, such as Dr. Shaywitz, attest to its effectiveness. Hence, as an unspoken compromise, they most often choose it as an intervention program as a sort of reading safety net.

The problem this creates is that many students do not show progress in the core program and need to be placed in the intervention program. Because it is understood that first grade students need to be finished or just about finished with RM Level II in order to attain 40 correct words per minute on DIBELS assessment, staff resources are strained. Some staff teach the core program, and some staff teach the intervention program.

I don't want to infect this analysis with a discussion with balanced literacy programs, but I can assure you if it weren't for the fact so many children in these schools are failing to learn how to read in a timely manner, the program of choice would be a balanced literacy program because such programs require even less teacher skill and knowledge that the big three basal programs.

So why is a reading program like Reading Mastery so difficult to teach to fidelity? Because Reading Mastery requires teachers to identify and correct each and every student mistake to enable each student to be taught each lesson to mastery. There is no such requirement (other than lip-service) in other programs. Other programs assume that kids will learn the material presented in each lesson even though the lessons have never been field tested in front of children. Some kids will get it, others will not. Those who don't get it are shipped off to a separate intervention program more attuned to their "learning style" with the slowest learners being labeled "learning disabled." In contrast, in Reading Mastery, the intervention is built right into the program. The teacher's responsibility does not end at the initial presentation. Rather, the teacher's responsibility ends at the students' mastery of the material, not before.

For our brighter students, understanding typical occurs after the initial presentation and with some practice, mastery typically follows. A monkey could teach such kids. A dumb monkey. And so could, I would hope, even an inept ed school graduate fresh out of school. It is not difficult to correct the errors of children who make few.

But as we move down the cognitive food chain, errors become more frequent and serious. And, teachers quickly realize that they do not know how to correct these errors reliably. Errors mean the student doesn't understand. Not correcting the errors means the teacher hasn't taught. And, when the teacher hasn't taught, you can bet the student hasn't learned. In this case, the student hasn't learned to read. This is why Reading Mastery is a demanding program to teach because, unlike other reading programs, it doesn't let the teacher off the hook when the student fails to learn. In short, it requires that teachers actual teach, not just the brighter students, but all students.

Since almost every schools has a population of non-bright kids who need to be educated in order to comply with NCLB, schools have two options to teach these kids:

1. Adopt a program like Reading Mastery which has an intervention built in and train your teachers how to use it; or

2. Adopt another core curriculum and enhance it, even though you have no idea how to enhance it in a way that guarantees that almost every student will learn (otherwise you wouldn't be in this predicament). You could always use a program like Reading Mastery as your intervention program.

Option two is not without its pitfalls as another educator pointed out in the discussion:

Staff need to be trained in how to effectively teach the Core curriculum. Because typical teachers who've graduated the past twenty years have rarely received effective training in how to teach phonics, from basic alphabetic principle to multi-syllabic word reading, the training to get teachers to effectively teach the core takes about two years through a combination of formal training and practice and in classroom coaching. You have to be prepared to make up for the deficits that students come out of ed school training with.

So, the first problem is that ed schools haven't adequately prepared elementary teachers how to teach reading or for that matter the proper underlying theory.

The core needs to be enhanced for at-risk learners. As part of training, teachers need to learn how to apply effective scaffolding through model-lead-test ("My Turn-Together-Your Turn") strategies; to maintain high reinforcement levels in the classroom; to effectively correct errors; to get unison responses from students; to teach lessons to mastery before moving on, etc. These strategies are not currently routinely used for regular education instruction. Open Court 1st grade is especially difficult to teach when long vowels are introduced. For example they present several different types of long e in the same week. Teachers have to put on the brakes and slowly move through those lessons.

Problem two, most core curricula are not carefully designed to parcel out instruction at an acceptable rate. Schools are still seen as sorting machines in which Herculean tasks are presented to children without regard to whether those not a the very tippy top can achieve the tasks.

All of the big 3 Phonics curriculum teacher guides have enough material in one day's lesson to last a week. Some of the suggested activities address critical reading skills - others include things like making Russian nesting dolls. We've found that many teachers have a penchant for opting for the Russian nesting dolls. Often critical reading skills are omitted (ex. words with tion suffixes are taught, but the suffix tion has never been taught in isolation.) We found that simply teaching the teachers to adapt the curriculum wasn't enough - that we had to write daily lesson plans based on the curriculum that teachers would use each day before doing the "other stuff." Thus, every day teachers knew which letter sounds to teach, which words to teach, which sentences from the story to practice, etc. In the beginning, we assumed that teachers would pick the quality comprehension activities, until we observed all of the Russian doll making. Thus we began including a list of research based comprehension activities from each day's lesson. These activities had to be completed before the "project stuff."

Problem three, when confronted with a choice of material, teachers often don't know how to pick out the material that will teach the important skills. Better to keep the slower learners occupied and docile, rather than go through the effort of teaching them. Projects and activities are good at keeping kids occupied.

Part of the training should include "deprogramming" reading mythology that teachers have learned in ed school. This is the most difficult part of the training for K and 1st grade teachers. Both Open Court and Harcourt encourage way too much sight word learning in kindergarten and first grade before students have acquired alphabetic principle. I've seen far both curricula taught as whole language programs by less capable teachers with a bit of phonics thrown in and the predictable/leveled books emphasized while the decodables were ignored. We trained teachers to omit the leveled books until alphabetic principle (50/15 on DIBELS NWF assessment) was established. Teachers need to learn how to appropriately select activities for the students in RM when they aren't in RM. It would seem obvious that you wouldn't give those students frustration level reading material outside of their instructional time, but I'm always surprised how often we have to intervene when teachers do that.

If your district does the above, they can improve reading results using the two curricula. We've seen that all of the big 3 can be credibly taught if adapted from the start. If your district is a high poverty one those adaptations are essential. Also we found that using Language for Learning in kindergarten with all of the children whether in RM or not will have immediate benefits as well as long term ones.

Problem five, educators need to know what they're doing to be successful. They don't. And, low-performers need explicit language training as well--something schools have historically relegated to the parents, i.e., they don't know how to do this either.

The more time in RM, the faster the students will progress. I suspect that all of the multi-tier programs don't plan for enough instructional time in the Intensive curriculum.

Lower-performers often need more instructional time, not less. See KIPP. If you enhance your program and do a poor job at it, as is most likely the case, you may have to cut into play time. You'll hear lots of complaints about this for good reason. If you just used a program like Reading Mastery in the first place, you wouldn't be in this predicament now.

December 18, 2006

The Song Remains the Same

Consider, for example, the meta-analysis of 2,575 studies of learning outcomes conducted by Fraser et al. (1987). These researchers studied the effect sizes assocaited with 27 instructional variables on learning outcomes. The four variables that yielded the largest effect sizes were reinforcement (Skinnerian rewards), acceleration (advanced activities for students with outstanding test scores on college-level selection tests) reading training (coaching programs in reading techniques), and cues/feedback (mastery learning principles). These variables yielded effect sizes of 1.17, 1.00, .97, and .97 standard deviations, respectively (Fraser et al., 1987). These instructional variables are far removed from the direct teaching of higher order thinking skills or cognitive functions ... In fact, the variables in Fraser et al.'s study that most approximated thinking skills training--higher order questions and advanced organizers--yielded effect sizes of .34 and .23 respectively (Fraser et al., 1987).

The Fraser et al. study is Synthesis of Educational ProductivityResearch, International Journal of Education Research, 11, pp. 145-252.

How is it that a profession finds itself in a position of being diametrically opposed to its own research?

December 17, 2006

Money solves all problems

Washington, D.C.'s schools spent over $15,000 a student, the highest level in the nation, in the academic year 2004-05, according to the National Education Association, and well above the New York level of almost $13,000. But District of Columbia students lag behind in testing, and schools are poorly maintained. Most parents who can afford to opt out, do so, either by moving to the suburbs or by sending their children to a private school.

If you can't teach children to read and do basic math with $15k, you won't be able to do it with $30k.

Oh, the shame

December 15, 2006

KTM on the Blink

Report Issued, Promptly Ignored

An independent commission yesterday proposed dramatic changes that would shake up American public education in an effort to make the nation more competitive globally. The recommendations include authorizing school districts to pay companies to run all their schools; enrolling many students in college after the 10th grade; and paying teachers about $100,000 annually.

There goes three radical and expensive suggestions with no proven track record of success. Who could have possibly issued such a report:

The 170-page report, "Tough Choices or Tough Times," is the result of a year-long study by the panel, which includes New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg; Joel I. Klein, chancellor of the New York City public schools; former Michigan governor John Engler, president of the National Association of Manufacturers; Roderick R. Paige, former secretary of the U.S. Department of Education; Marc H. Morial, president and chief executive of the National Urban League and former mayor of New Orleans; and D.C. School Superintendent Clifford B. Janey. It was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Lumina Foundation for Education.

A rogue's gallery of know-nothings who don't know how to educate children funded by a foundation that has taken nothing but missteps in its short history. What, no small school initiative?

The most controversial recommendations include empowering school districts to sign contracts with companies and teachers to run the schools -- which would replace schools' administrative structures with something similar to that in charter schools -- and forcing teachers to give up pensions in exchange for large pay increases.

Most companies don't know how to run schools effectively. Neither do teachers. Many charters are just as bad as similarly situated public schools, sometimes worse. And, paying teachers more just means we'll be spending more for the same results. As "radical" as these suggestions are, they are not so radical as to have identified and reformed the underlying problems in education.

Districts, they said, should relinquish control to the most highly qualified contractors, who would be rewarded for successfully running schools -- or fired if student performance languishes.

Today, we can fire administrators for poor performance, so what's the diff?

But Anne L. Bryant, executive director of the National School Boards Association, said hiring contractors to run the schools would create "a huge new set of enterprises that we have no evidence will work." Moreover, it would negate the administrative economies of scale provided by a central office and "add a great deal of costs to a school," she said. "We've seen that to an extent with charter schools."

But, if the plan would eliminate some of the self-interested nitwits, like Anne L. Bryant, who burden the system and have no incentive or responsibility to achieve results, it may not be all bad. To even suggest that there are administrative economies of scale in our current system demonstrates why people like this need to go.

Tucker said the recommendations would take 15 years to implement, but he predicted that they would result "in what will plausibly be the best national public school system in the world."

I will bet anyone any amount of money that if all these recommendations are placed into effect and everything else held constant that in fifteen years we'll have a more expensive schools system that performs just as poorly as the current one.

December 14, 2006

Unbelievable

The columnist discusses how schools have been banning honor rolls, rough play activities like dodgeball, and inflating grades and then somehow turns around and blames the parents for all this.

I've seen many overprotective parents who mollycoddle their kids, but the banning of dodgeball, the elimination of honor rolls, and grade inflation all originate with the schools. The problem, to the extent there is one, is that most parents meekly go along with such crazy things because they look to their schools as some sort of authority figures on education and related activities.

So what we have in affluent towns like Needham, Newton, Wellesley and Brookline are expensive tutors and SAT courses, private college consultants, one-on-one sports coaches and more therapists prescribing more anti-depressants to more 15-year-olds. Meanwhile, few are expected to clean up their rooms or walk, heaven forbid, the half-mile home after school. What we have in affluent towns - and this is about affluent towns - are overinvolved parents, hoverers, I call them, so busy greasing the skids for their kids that their kids cannot learn to fail. And they’re afraid to as well: What will mommy or daddy do?

Who hires a tutor for a student who is is doing well in school? Usually, the tutor enters the picture because the student is struggling in school, which is to say, the student is failing. The tutor is there so the student will stop experiencing failure. Stick with me here: students who fail become unmotivated and disengaged, students who are unmotivated and disengaged tend not to attend to their school work, kids who don't attend to their school work tend not to do well in school, kids who don't do well in school usually wind-up staying at mom and dad's house well past the point that mom and dad want them to, not to mention the fact that they probably won't graduate from college or be forced to take one of those easy majors, like journalism, which ensures the student will be in mom and dad's pocket for years to come.

But you can’t learn how to get up if no one lets you fall.

But you may stop getting up if you fall too much. It is a delicate balance.

December 12, 2006

The perfect article for rubberneckers

Are you the kind of person who's repulsed by, yet oddly attracted to, accident scenes while driving on the highway?

Are you the kind of person who's repulsed by, yet oddly attracted to, accident scenes while driving on the highway?If so, you're going to love this longish article in the St. Petersburg Times about the ninth grade experiences of four students from a bad neighborhood. (hat tip Sherman Dorn)

You get to read about bad family life, poor parental influence, drug and alcohol dependency, truancy, the obligatory toothache (score!), scads of emotional and behavioral problems, classrooms out of control, and a little hint of bad teaching.

Ultimately, however, the problem with such articles (and TV shows like this year's The Wire) is that we are only brought in after the crash has occurred to witness the carnage. When you're brought in this late to the game, it's difficult to piece together the true causes of the accident. These articles always make it clear that these kids crashed academically, but figuring out when or why is more problematic.

Bad family life contributes greatly to the problem and such deficiencies always shine through brightly in such articles. They overshadow (Ed: is that a mixed metaphor?) the other mighty contributor of the problem--the schools themselves.

And, it's not necessarily the schools these kids are in now. In such neighborhoods, middle and high schools are relegated to a triage and damage control function. Most kids are so academically damaged by this point that there's little a school can do to remediate (assuming they know how) because remediation at this age requires the assent of the student and most students aren't going to give consent. What's the point?

One of life's greatest ironies is that teenagers get to make most of life's biggest decisions. And, kids from these neighborhoods tend to choose wrong.

What I want to see is a documentary following two classes of kids from one of these bad neighborhoods. Kids in both classes would have the same family problems and poor academic preparation and poor parental support. The only difference would be that the first group would start out in kindergarten in a classroom which provides effective instruction while the second group is put into a typical classroom in which most of the kids will fail academically.

Then we'll track both groups through grades K-8 and see first hand the devastating toll that academic failure takes on the second group and how academic success serves to at least partially ameliorate the bad family lives of the first group.

People need to see how academic failure quickly grinds down the enthusiastic elementary school student in short order. People need to see the contrast between effective teaching and ineffective teaching and how that affects children. People need to see the car crash, not the aftermath.

New Way to Teach Penmanship

Educators are finally realizing the folly of not teaching kids the mechanics of handwriting.

Educators are finally realizing the folly of not teaching kids the mechanics of handwriting.Realizing that when kids have not been taught handwriting skills, problems frequently crop up in students' written communication. In other words, students who struggle with the mechanics of writing, because they have not adequately learned the mechanics of writing, have difficulty expressing themselves in writing because they must expend an inordinate amount of brainpower attending to the mechanics of forming the letters on the page instead of attending to the creative authoring skills.

Then, of course, there's the problem of not being able to take quick and legible notes in class which starts to become a problem at the high school level. As a result, teachers are going back to the time-honored practice of teaching handwriting skills as a sequence of basics skills and giving students sufficient practice in mastering those skills to the point of automaticity.

I'm only kidding. You don't really think that educators would ever do anything so sensible. No, there's an exciting new way to teach writing--Handwriting Without Tears-- in which kids learn handwriting skills through the use of:

wood blocks, puppets, songs and even dances.

Personally, I like the puppets the best. I almost had to resort to the hand puppets myself to get through the trauma of drafting this post.

I suspect that HWT will be popular with educators; it's directed to all their pet biases--silly manipulatives and activities. The hand-puppets are a bonus.

Read the whole story here and visiting Hand Writing Without Tears here. You'll also want to check out the obligatory "Research" paper in which nine of the ten pages are devoted to research that wasn't conducted on writing programs that weren't Handwriting Without Tears. The Handwriting Without Tears research is confined to two master's theses, one unpublished.

December 11, 2006

Who's the moron?

[N]o goal can be both challenging to and achievable by all students across the achievement distribution. Standards can either be minimal and present little challenge to typical students, or challenging and unattainable by below-average students. No standard can simultaneously do both—hence the oxymoron—but that is what the No Child Left Behind law requires.

Such an argument relies on language games and Rothstein's opinion that children cannot improve academically even if teaching is improved. Later in the article Rothstein let's us know what he thinks is possible to achieve.

We might, for example, expect students who today are at the 65th percentile of the test-score distribution to improve so that, at some future date, they perform similarly to students who are now at the 75th; students who today are at the 40th percentile to perform similarly to those who are now at the 50th; and students who are at the 15th percentile to perform similarly to those who are now at the 25th. Such goals create challenges for all students and express our intent that no child be left behind.Basically, Rothstein is saying that we can expect improvement of about ten percentage points or about 0.25 standard deviations through better teaching. Nonsense.

There is more than adequate research showing that we can reliably improve student performance by about a standard deviation, at least up until the end of elementary school. This means that a student performing at about the 20th percentile will perform as well as an average student today. Variation between children stays about the same, but the entire curve is shifted to the right. Then a state could play with the cut-scores and/or align the tests more closely with what is being taught and it's hard to see ho 90+% of kids cannot be made to perform proficiently on such a test.

And, since no current state exam (8th or 11th grade) tests anything that any well educated 8th grader should have mastered, schools have an additional six years of school to get kids to pass the 11th grade exam. That's six years to teach three years worth of material.

Rothstein conveniently reads too much into the definition of "challenging" standards. Most state tests today are simplistic, yet considered to be sufficiently "challenging" by DoE. Yes, I agree that the standards should be made more challenging for average and above students, but let's take this one step at a time. That fact of the matter is that standards are set sufficiently low that most, if not all, kids can meet them if they attend school regularly and are adequately taught.

Lastly, Rothstein doesn't seem to understand the concept, embodied in NAEP, that all kids can be proficient if they surpass the minimum proficiency level while preserving the innate variation between low and high performing students. High performing students will easily pass the test while lower performing students will likely struggle mightily to pass.

One day we'll hopefully raise the standards for our higher performers (a point SteveH makes all the time in the comments) to something approaching worlds class. That day couldn't come soon enough as far as I'm concerned. But such a raising of standards should not preclude schools from attaining the lower standards today and are certainly no reason for scrapping today's minimal accountability system.

December 8, 2006

Here we go again

It starts off bad in the very first sentence.

The No Child Left Behind education act, which requires the states to close the achievement gap between rich and poor students in exchange for federal aid, has been under heavy fire since it was passed five years ago.

Notwithstanding the loaded class-warfare language, this is not quite an accurate statement of the purpose behind NCLB. The purpose of NCLB (PDF), as defined in section 1001, is to:

ensure that all children have a fair, equal, and significant opportunity to obtain a high-quality education and reach, at a minimum, proficiency on challenging State academic achievement standards and state academic assessments. This purpose can be accomplished by—

(3) closing the achievement gap between high- and low-performing children, especially the achievement gaps between minority and nonminority students, and between disadvantaged children and their more advantaged peers;

NCLB is intended to ensure that all children receive a high-quality education so they reach proficiency based on challenging state standards and assessments. One way they can do this is by closing the achievement gap between low and high performing children. As I pointed out in this post, under NCLB the achievement gap is measured by comparing the number of children who are proficient to the number of children who are not. If all children are proficient there can be no achievement gap. NCLB does not, however, contemplate that low- and high-performing children will perform equally. That's an impossibility, especially if the standards are challenging as contemplated by NCLB.

After the editorial states the NCLB critics' position, and failing to point out that said position lack any evidentiary basis, this economically naive statement is made:

Unless we improve schools — especially for minority children who will make up the work force of the future — we will fall behind our competitors abroad who are doing a better job of educating the next generation.

No we won't, dummy. One advantage of having one of the most economically free systems in the world (thanks to not following the unfailingly wrong advice of the editors of the NYT) is that there is no shortage of well-educated foreigners clamoring to come to the good ol' U.S. of A to work. We have the ability to brain drain the rest of the world and we've been doing so for a long time now. (Just check out the Nobel Prize winners in science; there are two types: Americans and non-Americans who now live in America.) The only losers will be the native-born Americans receiving the inferior education who can't compete with the foreigners immigrating to America who received a better education. America won't lose, but certain American's will.

It’s impossible to brand No Child Left Behind as a failure, because its agenda has never been carried out. The law was supposed to remake schools that serve poor and minority students by breaking with the age-old practice of staffing those schools with poorly trained and poorly educated teachers. States were supposed to provide students with highly qualified teachers in all core courses by the beginning of the current academic year. That didn't happen.

Here the Times is confusing the term "highly qualified teachers" with "highly effective teachers." Very few of the teachers which NCLB considers to be "highly qualified" are also "highly effective" with low-performing students. Highly qualified means that the teacher has a certain teaching credential; however, that teaching credential does not guarantee that the teacher knows how to or is capable of teaching low-performing children.

The country would be much further down the road toward complying with No Child Left Behind if the Department of Education had given the states clear direction and the technical assistance they needed. Instead, the department simply ignored the provision until recently and allowed states to behave as though the teacher quality problem did not exist. Thanks to this approach, the country must now start from scratch on what is far and away the most crucial provision of the law.

This assertion is based on the fallacy that all it takes to successfully teach low-performing students is "highly qualified" teacher. The only thing that seems to reliably work to educate low-performers is the use of a well-designed curriculum, a staff of teachers trained in how to effectively use that curriculum, and administrators committed to making sure that the curriculum is well implemented. NCLB is silent as to all three of these requirements. It is up to the states to find what works and to use it. So far, the states, not unexpectedly, have proven incapable of performing this task.

The Times' big conclusion is:

Given what’s at stake, the teacher quality provision of No Child Left Behind deserves to be at the very top of the list when Congress revisits the law.

We should be grateful that the Times is not in charge of setting the policies or running our public schools. Lately, they seem even incapable of putting out a decent newspaper.

December 6, 2006

Tough Nuts

The generally reliable Eduwonk calls it the "[m]ost important education article written this year."

I must be missing something.

The Tough article is split into two parts:

[T]wo parallel debates about the achievement gap have emerged. The first is about causes; the second is about cures. The first has been taking place in academia, among economists and anthropologists and sociologists who are trying to figure out exactly where the gap comes from, why it exists and why it persists. The second is happening among and around a loose coalition of schools, all of them quite new, all established with the goal of wiping out the achievement gap altogether.

Tough gets the first part, the causes of the achievement gap, almost entirely wrong --no doubt because he relied upon the views of "economists and anthropologists and sociologists" from "academia."

Then he commits the sin of omission in the second part by focusing on one type of middle school school reform model, KIPP, which, though successful, requires students and teachers to put in long hours and a long a school year to make up for the poor teaching these kids received in elementary school.

But I'm getting ahead of myself.

Tough is 30 years late to the game with his stunning revelation that low-SES children are exposed to far less words at home as children than their higher-SES peers with the result being a vocabulary gap that continues to widen. Becker identified this phenomenon back in 1977 in "Teaching Reading and Language to the Disadvantaged—What We Have Learned from Research" published in the Harvard Educational Review.

In the analysis that follows, we conclude that schools systematically fail to provide instruction in the building blocks crucial to intelligent functioning, namely, words and their referents. Children from homes where there is strong adult support for refining the use of language are more likely to succeed in school than those from homes with less adult-child contact and adults with less education (Coleman, 1975; Freeberg & Payne, 1967; Glass, 1973).

Becker concludes:

The hypothesis that vocabulary-concept knowledge plays a major role in reading comprehension is supported in the research literature. In his review of research Carroll (Note 9) concludes thatmuch of the failure of individuals to understand speech or writing beyond an elementary level is due to deficiency in vocabulary knowledge. It is not merely the knowledge of single words and their meanings that is important, but also the knowledge of the multiple meanings of words and their grammatical functions. (p. 175)

Carroll also argues that vocabulary-concept knowledge is the key area of concern for improving reading comprehension for the economically disadvantaged, but he is quite aware that there is no easy way to make gains in this area. (emphasis mine)

Becker understood that it was the lower-IQ of these children and their parents that's at the root of the problem. Due to this IQ deficiency, these children picked up vocabulary knowledge at a slower rate than their higher-IQ peers and, unfortunately, "there is no easy way to make gains in this area" because it is extremely difficult to accelerate the learning of vocabulary in these kids due to the nature of learning vocabulary acquisition. (I wrote about the problem in detail here.)

In contrast, Tough draws this spurious conclusion.

Hart and Risley showed that language exposure in early childhood correlated strongly with I.Q. and academic success later on in a child’s life. Hearing fewer words, and a lot of prohibitions and discouragements, had a negative effect on I.Q.; hearing lots of words, and more affirmations and complex sentences, had a positive effect on I.Q. The professional parents were giving their children an advantage with every word they spoke, and the advantage just kept building up.It's not just the exposure to vocabulary that is problematic; it's also that these kids are acquiring vocabulary at a slower rate than their middle class peers. This is a function of IQ which Tough is too quick to dismiss. After reviewing some more correlative "research" Tough draws this final conclusion as the summation of why the achievement gap exists.

Taken together, the conclusions of these researchers can be a little unsettling. Their work seems to reduce a child’s upbringing, which to a parent can feel something like magic, to a simple algorithm: give a child X, and you get Y. Their work also suggests that the disadvantages that poverty imposes on children aren't primarily about material goods. True, every poor child would benefit from having more books in his home and more nutritious food to eat (and money certainly makes it easier to carry out a program of concerted cultivation). But the real advantages that middle-class children gain come from more elusive processes: the language that their parents use, the attitudes toward life that they convey. However you measure child-rearing, middle-class parents tend to do it differently than poor parents — and the path they follow in turn tends to give their children an array of advantages. As Lareau points out, kids from poor families might be nicer, they might be happier, they might be more polite — but in countless ways, the manner in which they are raised puts them at a disadvantage in the measures that count in contemporary American society.

There is no evidence that if you give a low-IQ kid X, then you're going to get the same Y back that you get back that you get from giving X to a higher-IQ kid. Not to mention the sticky problem that lower-IQ parents have never been shown to be capable of providing X to their children and for that matter neither have schools. Again, Becker, nails the problem much better than the naive Tough:

These logical and empirical analyses clearly point to a problem for educators who strive to teach reading comprehension to all children. The data suggest that school programs do not systematically build vocabulary-concept knowledge. Current programs are structured to teach middle-class children or children who, to a large extent, are taught oral-language comprehension at home. We assume that this form of language learning is then transferred to reading comprehension at school. (emphasis mine)

At best, Tough has partially identified the problem facing low-IQ kids (vocabulary acquisition deficiencies), but fails to recognize that merely identifying the problem does not imply an instructional remedy to solve the problem. Tough never does attempt to find an instructional remedy to the vocabulary acquisition problem. Instead, he races off to find and analyze a school that has gotten some results with at-risk kids. The model he picks is KIPP.

Now I like KIPP and think the model has accomplished some impressive results. But, the KIPP model is not without its problems. KIPP is a middle school reform model. As a result, when kids enter KIPP they are far behind. Part of KIPP's solution is to the extend the instructional time offered to students by extending the school day, week, and year. This is not an ideal solution. Why wait until fifth grade to intervene? Why allow these students to be mistaught and not taught for their first five school years before intervening? Perhaps it becomes necessary to teach for long hours following such a delay, but perhaps KIPP is not teaching as efficiently as it could. Maybe if KIPP started in K, they could get away without having to increase the instructional time.

Other instructional reform models manage to increase the academic performance of at-risk children without extending the instructional time offered. For example, the DI model only requires about 3 hours of instructional time per day in reading, math, writing, spelling, and language to get kids performing at grade level by first grade and keeps them there until the end of elementary school- fifth grade. Kids coming out of the DI program in fifth grade can then be taught in a more traditional manner in middle school and high school without the need for increasing their instructional time burden.

In short, it may be that the KIPP model is not scalable as Tough suggests, but that does not mean that other reform models have the same infirmities. In this respect, the second part of Tough's article sets-up a false dilemma and a strawman, which he allows Rothstein to take a whack at, by suggesting that the KIPP model is the only successful reform model and by failing to note that some of the scalability issues inherent in the current KIPP model might be mitigated if KIPP started in elementary school like other successful reform models.

Then Tough concludes with a series of half-baked inferences from his discussion of the KIPP model. Here's the most egregious:

the reality is that even the best, most motivated educator, given just six hours a day and 10 months a year and nothing more than the typical resources provided to a public-school teacher, would find it near impossible to educate an average classroom of poor minority students up to the level of their middle-class peers.

There is absolutely no evidentiary support for such a conclusion. Counterexamples abound in the research literature. There are well over a hundred DI implementations that achieve KIPP-like results in a normal school day and year with typical teachers found in poor minority neighborhood under typical funding levels. Tough was either too lazy or too dishonest to go out and fund these schools or schools like them. No one wants to admit that most schools are adequately funded today. Now, that story would be worthy of being story of the year.

Engelmann Interview

Whether you agree or disagree with his teaching methodology, there is no arguing that Englemann's brand of instruction has proven to be very effective in inducing learning in almost any child. Engelmann takes a very scientific and logical approach to teaching children and is probably one of the best designers of instructional material we've ever seen. And, as opposed to most of the other educational theorists out there, his theories, as embodied in his instructional programs, have been proven to be effective and replicable under experimentally sound conditions.

And, I've yet to find a legitimate counterexample proving that Engelmann's methods don't work as they've been shown to work. What I usually see is the kind of unsubstantiated opinions that Mr. Person (who should be on your must read list) has been turning up over at TextSavvy. It's a lovely hypothesis as far as it goes, but you have to prove it's true for it to be valid criticism.

In any event, Engelmann has given us one successful and effective way to teach children, especially low-performing children who are otherwise unteachable. This is not to say that other successful ways to teach do not exist, especially when you confine your teaching to average and high-performing kids. Engelmann's theories serve as a strong foundation for understanding education related issues for the simple reason that they've have some validation behind them.

You would do well to watch the entire six-part hour-long interview and then re-watch it until you understand what he's saying. Bear in mind that this is raw interview footage. I've summarized each clip for those of you who want to jump around to the more interesting parts.

Clip One -- how Engelmann went from advertising executive to instructional designer; a discussion of the famous chicken sexing experiment; why development theory isn't useful to instructional design.

Clip Two -- The Bereiter-Engelmann preschool and their first failed reading program; fallacy of using picture cues for helping kids learn to read; why DI is and structured the way it is, i.e, so that teachers are able to identify and correct students' understanding.

Clip Three -- Logical analysis and sequencing of instruction; the reason for field testing instructional programs before releasing them; teaching fractions and why to avoid using manipulatives when teaching math; why not to teach misrules; the retention of taught material and amount of practice needed for mastery; teaching of irregular words and sequencing of instruction.

Clip Four -- Low performers compared to typical middle class kids; difference is primarily language related; many lack the critical language needed to teach them because they do not know the meaning of many words the teacher assumes they know; why good practices aren't accepted in education; criticisms of DI; educators do what they want regardless of whether students are learning.

Clip Five -- Educators as elitists; installation of unsound practices by fiat; why DI uses a scripted program; project follow through; problems implementing DI in inner cities.

Clip Six -- Teacher problems and deficiencies in their math skills; criticism of certifying agencies; turning schools around; problems with placing transfer students, problems with state tests like the pre-2003 Maryland state test; consumer advocacy for schools; and criticism of the high-scope study.

Too much opinion, too little theory

Because education is not yet a mature profession, no one bothers to validate these crackpot opinions via the scientific process. Educators nonetheless often label these unsubstantiated guesses or hunches as theories. They are not.

Theories are not merely someone's opinion, even though that is how the word is often used in everyday speech. Even if that person appears to be an authority figure, their opinions do not magically become theories. In education, there are precious few authority figures at the K-12 level in any event. Most educators simply do not know how to induce learning in kids who are not part of the portion of the top of the bell curve which always has managed to learn no matter how poorly or superbly the material is presented to them. Educators have been much less successful in inducing real learning in the remainder of kids. Without this success in educating, there can be no authority. This is the difference between an opinion and a theory; a difference that is not understood by most educators.

A theory is a logically self-consistent model or framework for describing the behavior of a related set of natural or social phenomena. It originates from or is supported by experimental evidence. In this sense, a theory is a systematic and formalized expression of all previous observations that is predictive, logical and testable. Most opinions given by educators have either never been tested or have failed under somewhat rigorous experimental conditions. The result is that these opinions are not reliably predictive of what works in education.

The fact of the matter is that educators, for the most part, don't know how any kid really learns. What they do know is that some kids do learn. Then they form opinions based on their observations of these successful learners. The result is that the opinions, coming from those who are naive observers about educating since they don't truly know how to induce learning, often prove to be wrong. This is to be expected.

There is no shame in being wrong. Scientists often have hypotheses that prove to be wrong. Science progresses slowly in fits and starts and through lots of trial and error. There is no shame in saying that you don't know something or how something works. What is shameful is professing that you do know something, when in fact you don't. What is especially shameful is when you do this by circumventing or perverting the scientific process. You don't to pass off your opinion as a theory when it is not. If you try to do this in most of the legitimate hard sciences and engineering fields, you will be recognized as a fraud by your peers and discredited. In education, however, most of the theorists are frauds. What we have is a bunch of foxes guarding the hen house. There is a critical mass of frauds in education that prevents the peer review process from working as it should to discredit failed or untested hypotheses being passed off as theory.

In education, there is no distinction between opinion and theory. All opinion is passed off as legitimate theory. It is almost impossible to for a non-educator to determine what worked from what doesn't work in education. It is virtually impossible to separate opinion from theory. Journalists fall prey to this charade all the time and it does not help that they often have the same agenda and biases as educators. Journalists help perpetuate the spread of misinformation in education by giving credence every crackpot opinion they get from educators with which they happen to agree.

So what's a non-educator to do in such a hostile environment?

Be sceptical. Assume that everything you are told or read is merely opinion, unless proven otherwise. Assume further that the opinion is wrong, unless the opinion has resulted in children have increased their learning by an educationally significant amount under reasonable experimental conditions. Make sure that these kids were not "natural learners" who would have learned no matter what. Discount all appeals to authority. It doesn't matter how many books the person has written, if he is a professor at a prestigious Ed school, a teacher of thirty years experience, a member of some prestigious education group or think tank. It only matters whether that person has achieved results or is drawing a reasonable inference from someone who has. Such a framework allows you to safely ignore 95% of all the garbage opinion out there.

So wipe your mental slate clean. Forget what you know or think you know about education. Most of its is likely wrong. From now on be fastidious about what you let in. Keep out the garbage. No matter how appealing you think an opinion might be, don't let it affect your thinking until you've validated it. When you find something you think is true, look for counterexamples that cast doubt on it.

You'll soon see that education is not nearly as complicated as you've been lead to believe. What you'll see is that what works in education is consistent and predictable.