- Poor kids often come to school far behind their middle class peers in reading ability, can this initial achievement gap be eliminated in a timely manner?

- Can this initial achievement gap in reading ability be eliminated by a school-based instructional intervention?

The study is Academic Acceleration in First Grade Reading Using the Direct Instruction Model by Michael Rebar answers both questions in the affirmative.

I alluded to this study in an earlier post on Douglass High. As I indicated in that post, in the mid 90s Baltimore decided it would mandate the use of SRA's Open Court reading program in all its public elementary schools. At the same time, The Baltimore Curriculum Project contracted with the National Institute for Direct Instruction (NIFDI) to provide training, coaching, and support for reading instruction in eleven Baltimore schools.

This set up the conditions for a nice experiment. Eleven Baltimore City schools were found with similar demographics and achievement levels to the 11 NIFDI schools to serve as controls. Thus, the study involved three groups: the 11 NIFDI schools, the 11 matched control schools, and the remaining Baltimore schools. In total, between 1998 and 2003, 41,223 kindergartners and first graders in Baltimore participated in the study.

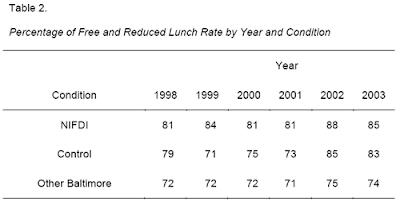

Here is the demographic break-down for all three groups:

The above table shows the average percentage of poor students (based on free and reduced lunch participation) in the NIFDI schools, the control schools, and the remaining Baltimore schools for each year of the experiment (1998-2003). As you can see, the poverty rate in Baltimore is high (about 72%) but the poverty rate at the NIFDI and control schools was even higher -- these were some of the poorest schools in the district. These schools were also the likely feeder schools for Douglass High.

The experiment was phased in over three years -- 1997-1999. Five additional schools initially chose to implement the NIFDI model, but dropped out; they are included in the Other Baltimore group. The number of schools in the Other Baltimore group varied between 103-122 schools.

In the spring of 1997, the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) was administered to kindergartners in the NIFDI and Matched Control conditions. The PPVT is a widely used norm-referenced picture identification test that is highly predictive of future reading ability. The results serve as the best estimate of initial achievement reading level (i.e., prior to intervention).

The NIFDI schools received two 30 minute periods of reading instruction per day in K and 1. The curriculum was Reading Mastery Classic. The NIFDI schools also received an additional 30 minute period of language instruction using the DI program Language for Learning and Language for Thinking which focus on oral language development.

Prior to 1998, the Matched Control and Baltimore condition schools were free to use any curriculum program desired. There was no district-wide structured reading program and schools used a variety of instructional programs. In the fall of 1998, the district adopted Open Court Reading in kindergarten through second grade.

Let me translate that into English. Prior to the experiment, Baltimore schools taught Reading in whatever manner they desired with predictably bad results. In 1997 Baltimore schools were performing at the 27th percentile on the PPVT. In 1998, all but 11 of Baltimore's schools switched to the research-validated Open Court Program. The remaining 11 schools switched to DI under the guidance of NIFDI. Thus, the experiment allows us to make three comparisons: 1. between DI and Open Court, 2. between DI and the pre-experiment reading curricula, and 3. between Open Court and the pre-experiment reading curricula.

In the spring of 1998 and 1999 the Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills, Fourth Edition (CTBS/4) (CTB,1991) was administered to all Baltimore first graders. The Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills, Fifth Edition (CTBS/5–TerraNova) was administered to all first graders in 2000 through 2003. Here are the results., including the PPVT baseline results.

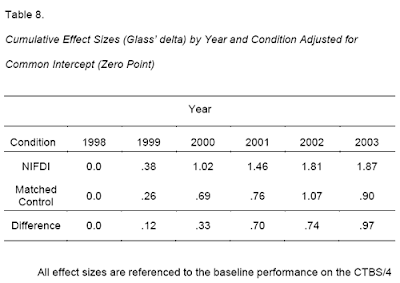

The NIFDI schools went from the 15th percentile in 1998 to the 75th percentile in 2003, a significant increase in student achievement. In contrast, the Matched Controlled schools (using Open Court) went from the 14th percentile in 1998 to the 40th percentile in 2003, also a significant increase, but not as much as the NIFDI schools. The Other Baltimore schools (using Open Court) went from the 24th percentile in 1998 to the 59th percentile in 2003, also a significant gain. Here are the effect sizes for each group.

As you can see, the NFDI intervention had a very large effect size of 1.87 standard deviations. Let's put this in context. The NFDI intervention was 750% more effective than lowering class sizes to 13-17 students. In fact, since most non-instructional interventions perform about as well or worse than lowering class size, the NIFDI DI intervention was at least 750% better than those as well.

Even the Matched Control Open Court schools had a large effect size of 0.90 standard deviations or 360% more effective than lowering class size. That's not too shabby at all.

Below is a graph of the NIFDI schools showing performance gains in normal curve equivalents.

Here's the analysis from the study:

The average student performance level in the NIFDI schools moved from the lowest quintile to well above the national mean. All NIFDI schools showed substantial achievement gains and several became beacon schools for the district. The three highest achieving schools in the district in 2003 were NIFDI schools. The Matched Control schools never achieved a mean score above the national average.

In all, 49 of the 103 Baltimore condition schools (48%) achieved a mean Total Reading NCE score of 55 or greater in the 2003 school year. In the NIFDI condition, ten of eleven schools (or 91% of these schools) reached this level. Only one of the eleven Matched Control condition schools reached an NCE score of 55; this school ranked 49th in the Baltimore condition.

The Fisher’s Exact Test indicates that schools in the NIFDI condition were significantly more likely to exceed the national mean than either the Baltimore or Matched Condition schools. The three highest achieving elementary schools in the district were NIFDI schools, achieving mean Total Reading NCE scores of 92, 90, and 83. The highest three schools in the Baltimore condition achieved scores of 78, 76, and 75. It is perhaps ironic that the highest achieving Baltimore school (with a mean NCE score of 78) is one of the DI schools that did not continue as a NIFDI school but continued to use the Direct Instruction reading program.

There you go. The top four schools in Baltimore were all schools using DI. Of course, the Baltimore schools, despite a long history of academic failure, still though they knew the best way to teach:

Despite the gains demonstrated with the NIFDI model in Baltimore in 1997 through 2003, the district did not systematically expand the model to other schools. In fact, during the course of this study the district mandated procedures that were at odds with model provisions. Teachers were required to attend district inservice trainings that advised them to do things differently than what the NIFDI model specifies. The central administration required schools to provide daily test-preparation periods for the entire school year. NIFDI advised the principals in their model not to do this because it believed greater gains would be possible by implementing the model rather than providing test preparation (which would also tend to artificially inflate achievement scores). In fact, the six principals who implemented the model most faithfully and ignored some of the district mandates achieved better performance than any of those who complied with district regulations.

So what do you think Baltimore did when faced with these improved scores?

That's right, they stopped the program and went back to what they were doing before the intervention. Unfortunately, I've been unable to find CTBS scores from 2004-2008.

So the answer to our initial questions is: Yes, we can eliminate the achievement gap between low-SES students and their middle-class peers in reading by the end of first grade by means of a school-based instructional reform. In fact, we can get low-SES kids to significantly outperform their middle-class peers. These achievement gains can be accomplished without any SES-based reforms or by reducing any of the symptoms associated with growing up in a low-SES environment.

So, how do all you Broader, Bolder types explain these results?

59 comments:

KDeRosa said

That's right, they stopped the program and went back to what they were doing before the intervention.

I don't understand. Which schools went back to previous programs? The NIFDI schools, or the Baltimore school district? Did they stop using Open Court, or Reading Mastery?

I thought the NIFDI schools had to continue to use Reading Mastery since they are charter schools under the control of the BCP.

The non-NIFDI schools in Baltimore were either allowed to drop Open Court or weref orced to adopt something else, not sure which was the case.

Some of the schools failed to follow NIFDI's implementation guidelines and NIFDI stopped working with some of the schools in 2002.

what about the BCP schools? Aren't they still using DI since they're charter schools?

(I'm not sure I understand what the BCP really does.)

A mean score at the 75th percentile is a “gee whiz” statement, and the NIFDI schools did perform considerably better on the CTBS than the comparison schools. But reporting only the mean without any mention of the variability among schools, teachers, and students spins the results.

The graph of the 11 NIFDY schools indicates large variability among schools,with means ranging from the 30th percentile to the 90th percentile. Some schools leaped while others limped.

Even a mean at the 90th percentile leaves some kids with “reading problems,” albeit the CTBS is an insensitive measure of what teachers have taught and what kids have learned.

The median school score is closer to the 60th percentile which deflates the “whiz” value. The high performing schools do suggest that with further initiative the kids who are struggling in reading in grade 1 could be subsequently taught. The interesting questions are who was minding the store in the schools where a much higher proportion of the kids were struggling and who was minding it when the District dropped DI despite it’s relative superiority. The cited study sheds no light on these questions.

Dick,

You seem to paint an overly doubting/pessimistic view on the study. Yes, one school ended up in the 30s, but most were 50-70 percentile, and there were 3 superstars.

Given where they started, these statistics are impressive. Also, given an attitude that these students can't be educated without some major social program (i.e.,preschools, etc.) the results are quite significant. They also say that perhaps schools have a shot at the 90% if they can learn from these top 3 schools.

Yes, some kids are left out. But I'll bet it's a lot better in these schools than it used to be.

I'm neither "doubting nor pessimistic." Just trying to clarify the findings.

I just noted that Ken does provide a link to the full report. It does include standard deviations for the NIFDI sample and for the individual 11 schools and attributes the differences to "differences in the fidelity of implementing the model."--a nice way of saying that the "model" didn't work in some schools.

Whether the fault was with the "model" or the personnel, the interesting questions remain. And irrespective of the answer, NIFDI first graders were still struggling with reading in each school.

It's not possible to get every student up to speed in some of our urban schools, regardless of the curricula or quality of teaching. Some schools have a pupil turnover of 50% or even more during the academic year. I was in one where every class had transfers in and out amounting to about 10% every month; on average 3 students per month coming and going in each class. We had a couple of homeless shelters and battered womens shelters in the area, as well as two housing projects. By year's end, the class had only about a quarter of the students who started the year in September.

So, however well the teacher taught, every month or so there would be new children who had not had the benefit of the instruction that other students had. Often these would be students who were months or years behind the work for the grade. Even with immediate, and effective, intervention, those students' results would be less than impressive on end-of-year tests. These kids are certainly teachable, no question, but getting good results when they are only with you for a couple of months at most is problematic.

Even though there were some really effective things going on, our testing didn't show this because of the constant flux.

One way around this is the kind of individual data they use to track student progress in Tennessee. If you look not just at group scores but at fall and spring results for individual students, you get a better picture of whether a school is effectively teaching all kids. In fact you could get entry/end of year data on children who transfer in and develop a pro-rated (if that is the right word) figure for whether they are making good progress. We did this informally and found that new students, even ones who were seriously delayed, made good,sometimes dramatic, progress, if they were with us for 6 months or more. But our test scores didn't show this because the students were still well below level.

Unfortunately, in some communities high mobility rates make it difficult to ensure that all first graders (or second graders or any other graders) are successful regardless of what the school does. It doesn't mean we aren't obliged to work our ****s off but it does limit the effectiveness of even the best teaching or curricula.

Some districts try to address this by having the same programs used in each school (even down to what page you are supposed to be on on what date), but my experience suggests this would not work very well, because we were near the border of three different districts, so transfers were from all over. It would be impossible and probably not very effective to try to impose uniformity everywhere. And we all know that just telling people to use program x or y doesn't mean that they will do it, or do it effectively, or even that it is the right thing for the particular students.

Group results have their uses but I would like to see individual data also made public (not with kids' names, of course). The ultimate test is whether individual kids are learning, and how much. We should be looking at individual data not just percentiles or group composites, IMO.

But I think the issue of kids who move schools a lot - we have children in second and third now who have attended 20-30 schools- needs some attention. I haven't heard or read about anything that seriously addresses it.

"The ultimate test is whether individual kids are learning, and how much. We should be looking at individual data not just percentiles or group composites, IMO."

Amen--squared. Standardized achievement tests simply do not provide a basis for doing this, even with "value added" statistical adjustments or beginning and end of year testing.

What is required is a set of measures that track the acquisition of reading capability independent of grade. Such indicators directly resolove the matter of "mobility"--which indeed confounds currently available reading achievement statistics.

The methodology for constructing indicators that are sensitive to the structure of given programs is readily available and is much less complicated than the Item Response Theory and practice that characterizes currently mandated achievement tests.

Teach3rd said: "Even though there were some really effective things going on, our testing didn't show this because of the constant flux."

Comparisons of standardized test statistics provide sound indicators of program or institution effectiveness, unless there is some reason to suppose that the student populations of the tested programs or institutions difer systematically. That is, even with statistical noise induced by student mobility, unless this factor differed systematically between schools, differences in aggregate performance indicate differences in program effectiveness.

Dick Schultz said: "Teach 3rd said:'The ultimate test is whether individual kids are learning, and how much. We should be looking at individual data not just percentiles or group composites, IMO.' Amen--squared. Standardized achievement tests simply do not provide a basis for doing this, even with "value added" statistical adjustments or beginning and end of year testing."

This is mysticism. A measure is an order relation on a set. A test is a procedure or device for establishing a measure. A standard is a unit of measurement (e.g., a kilogram weight, a meter stick). Standards permit inter-group comparison. That is their purpose and the reason defenders of the US State-monopoly school system oppose them.

Group results have their uses but I would like to see individual data also made public (not with kids' names, of course).

The difficulty with releasing individual data, without kid's names, is that it is possible to track down individual kids that way even without knowing their names. For example, if you know the month and year a kid arrived at a school and their age, in many schools it would be possible to figure out who the kid is.

And of course, what data you need depends on what question you are answering. If the original question is "can poor kids initial achievement gaps be eliminated by a school-based instructional intervention, or is it outside the control of any school", then group-based data is perfectly adequate.

For a graduate student out there . .

It would be interesting to see what variables affected school performance in the NIFDI group. If you could find data, a few regressions would tell you a lot. Also, an analysis of policy would be interesting also. Did the more successful schools handle turnover better? Did they just have more "buy in"? (available via teacher survey)

Great post, with a good debate by the commenters

“A measure is an order relation on a set. A test is a procedure or device for establishing a measure. A standard is a unit of measurement (e.g., a kilogram weight, a meter stick). Standards permit inter-group comparison.”

Precisely. Let’s parse this to distinguish myth from reality, using reading instruction as the breadboard.

A standardized reading test is an ordered relationship of items constructed to yield a statistical scale. It is not grounded in what has been taught and does not yield any direct information regarding what has been learned. The tests are ungrounded. (e.g. no analog to a kilogram weight or meter stick).

While the tests do permit inter-group comparisons, the comparisons are sensitive to SES characteristics, not to differences in instruction. The resulting correlation of standardized tests (irrespective of subject) with SES is commonly misinterpreted to conclude that SES “causes” academic achievement.

Let’s try a different view. Think of a set of kitchen devices such as measuring spoons and cups. They meet the formal characteristics. Psychometrically, they constitute a Guttman scale—an ordered set that cumulatively increases in what is being measured.

In reading instruction, the instructional aspiration is the delivery of a student who can read any text with understanding equal to that were the communication spoken. If the measures includes lexicon likely to be within the spoken vocabulary of children, that makes the measurement SES-fair. The measures can draw on at least 5000 words, quite an ample repertoire.

With this orientation it’s easy to determine if and when a kid “can read.” You can have as many “multiple forms” of text as you wish. Put one in front of the kid’s face. If the kid can read it and tell you what it’s about, the kid needs no further formal instruction in reading per se. Kid still has a lot to learn but the reading expertise that has been acquired now provides a means for independent learning.

The “hard part” deals with the kids who “can’t read.” But that strikes at the heart of instruction, not measurement. It’s a reasonable expectation that a “reading program” should be able to specify 5-9 ordered elements of a behavioral set that operationally defines the route for reliably delivering “readers.” There are reading programs that can do this. Where it can’t be done, it’s an unaccountable pseudo-program.

Simply registering attainment on the ordered set of Key Performance Indicators provides a sound basis for inter-program, teacher, school, and other administrative unit comparisons, and also comparisons on the usual biosocial categories of interest to the government or citizenry.

Individual student performance information need not go beyond the bounds of parent-student-teacher-school communication, so personal privacy is protected. The transparency of the measurement addresses the matter of “mobility”—The student’s instructional expertise travels with the kid, and instructional status can be verified at any time.

This orientation is “novel” only in educational measurement. It’s the basis for “Business Intelligence” and is equally applicable to reading and math instruction in particular. It’s unobtrusive and inexpensive. The psychometric community and the testing industry, however, have proved resistant to change. So the defenders of the U S. monopoly testing system are unlikely to embrace the orientation.

Dick says:

This orientation is “novel” only in educational measurement.

Agreed. In fact, using any kind of data to drive decisions could be considered "novel" in education.

Dick Schultz wrote: "A standardized reading test is an ordered relationship of items constructed to yield a statistical scale. It is not grounded in what has been taught and does not yield any direct information regarding what has been learned. The tests are ungrounded. (e.g. no analog to a kilogram weight or meter stick)."

We disagree. A standardized test is a test which expresses it's result in terms of a standard (a unit of measurement). Suppose you want to "measure" the height of children in a class. You can have them stand side-to-side against a wall. Starting at the left-hand end, you have them stand back-to-back and, if the child to the left is taller, change places. You then have the second in like stand back-to-back with the third-in-line, and switch if the child to the left is the taller, and so on, to the child at the right-hand end. If any children changed places, you go back to the left-hand end and repeat the procedure until there is no movement. You have constructed an order "as short or shorter than" (reading from left to right) or "as tall or taller than" (reading from right to left. You could use a seesaw and a similar procedure to "measure" the weight of a class of students. This is NOT a "standardized" test.

Now suppose that the school's basketsball coach wants the ten tallest girls in school to try out for the team. The coach could request the tallest girl from each class, but this procedure is inexact, since all the tallest girls might be in the same class. He could gather all the girls in the school in one room and repeat the procedure, but this would require a lot of time and a very large room. Or, he could take a stick, make one copy for each teacher, have each teacher express each student's height in terms of multiples of the length of that stick, and write each student's name and the number of multiples on a card. Such a stick is a "standard". Then the coach could order the cards (and therefore the students) by the numbers on the cards. THAT is a "standardized test".

This says nothing at all about why the students are taller or heavier.

The "unit" of measurement can create a dichotomous partition of the set, like a mark on a wall ("send to the gym everyone whose crown is above that line"). The unit of measurement can be a score (tally) of correctly answered vocabulary questions, derived from the performance of some reference group. That is, the median (or some other score) of the test compiler's sample group is called the "age-level expectation".

Again, all this says nothing about the cause of differences, between groups, in aggregate statistics of measures of height, weight, or reading vocabulary.

"It is not grounded in what has been taught and does not yield any direct information regarding what has been learned."

At the end of the year, are the kids in school A heavier, on average, than the kids in school B because of the school lunch program or because of breakfast and dinner at home? The test doesn't say. The inference that test score differences are caused by school differences depends on the supposition that the samples were large enough and didn't, in aggregate, differ significantly in their out-of-school characteristics.

From Teaching Needy Kids re implementation probelems during the BCP:

Note that in 1998, City Springs, Arundel, Federal Hill, General Wolfe, and Hampstead Hill were in their second year with NIFDI. That's why City Springs was no longer below the 10th percentile. In 2002, all schools but one were above the 50th percentile; 9 schools were above the 60th percentile; and 4 schools, more than a third of the schools we worked with--achieved at or above the 80th percentile. In 2003, all schools performed at or above the 50th percentile.

Some of the schools did not show did not show great improvement. The worst was General Wolfe, which had almost an annual succession of principals who ranged from poor to very poor. Ironically, though this school was only a few blocks from City Springs, it served a population of children considerably higher than that at City Springs.

Arundel did not reach its potential. It acquired a new principal who did not implement the program wholehartedly as the former principal had. AlthoughArundel slipped, several schools were performing in the same range as City Springs--far above average.

...

How did the district respond to [the success of the NIFDI schools]? It didn't exactly deny the outcomes, just tended to trivialize them. The district had what some of called a bad case of premature elucidation and assumed it didn't need to master the details of how to manage and maintain a successful implementation before doing it. The superintendent took over one of schools and ran it herself, but with higher funding than ur schools. The performance in this school slipped. The district took over most of our other schools and managed them through a department whose head knew far less about instruction than he would have to know to improve poorly implemented schools or maintain the higher schools at the level they achieved. The district implemented its model of managing and supervising these schools. Student performance slipped.

"A standardized test is a test which expresses it's result in terms of a standard (a unit of measurement)"

Really? What is the unit of the metric? It's certainly not height or weight. The examples given are a red herring.

The theory and practice of standardized achievement testing posits a “latent trait” that is univariate, homogeneous, and exists in varying amounts in examinees. Reading, math, and achievement in other school subjects are not in any way a trait,let alone a latent trait. And the phenomenon of interest is anything but univariate and homogeneous. Achievement does vary in amounts in individuals, but the phenomenon is transparent. I can’t off-hand think of any other sector of life where measurement addresses ungrounded “latent” phenomena.

Where instructional measurement currently falls short is in the thought given to what constitutes the structure and substance of the means for delivering aspired instructional accomplishments. That’s left up to individual teachers and unreliable delivery is attributed to deficiencies in students, family, or society—anything but instruction.

“Data” ARE currently driving consequential educational decisions. Teachers and principals are losing their jobs, students are being “gamed,” the curriculum is being narrowed, and so on. The novel ty in education is that these “data”and“decisions” are not yielding any fundamental changes in any aspect of “content standards,” instruction, or measurement. “Gains” are being trumpeted, but they are spotty and inconsistent and what they represent that is observable is not at all clear.

I’m sure there are teachers, schools, and districts where data are used to self-correct and improve instructional accomplishments, but they are isolated exceptions rather than the rule.

The rule is closer to the Baltimore situation that Ken describes. All accomplishment data are ignored and the show relies on idiosyncratic personal beliefs and preferences.

This shows the main problem with test-based accountability movement. The NCLN accountability scheme is simply insufficently robust to force schools into the drastic changes needed to improve achievement.

That's NCLB rather than NCLN isn't it Ken? Trying to "force" schools or people to do anything via "sanctions" has proved to be a losing strategy--and not only in education.

"Regime change" doesn't work any better in education than it does in international affairs.

The changes required to achieve the aspired accomplishments of NCLB are quite modest technically. Kids have the necessary human prerequisites and teachers and other ed personnel are "qualified."

Different measurement orientation and apparatus is required, but the remodeling involved is simpler, less obtrusive, and less expensive than prevails.

The onus of "accountability" needs to be shifted to the purveyers of instructional product/protocols and to the administrators charged with making instruction work. That's as it is in every area of life other than el-hi education.

The daunting obstacles are political rather than technical. Powerful interest groups both inside and outside the profession are being well-served by the status quo.

Rhetoric rules. As long as "proficiency" is viewed in terms of arbitrary cut-off scores that change with age/grade and "success" is viewed in terms of a "high percentile," kids, teachers, and citizenry don't stand a chance.

The theory and practice of standardized achievement testing posits a “latent trait” that is univariate, homogeneous, and exists in varying amounts in examinees.

I think you meant to refer to standardised aptitude tests. Standardised achievement tests are aimed to measure what people have achieved, not what their latent ability is. For example, the driving test measures driving ability, not how hard it was to learn to drive. A standardised blood sugar test measures levels of sugar in the blood but does not directly say if those levels are due to a fully functioning pancreas or insulin injections.

Standardised achievement tests of course posit a "latent trait" - there's no point in measuring something that no one can achieve. So we have standardised achievement tests for reading and driving, and blood sugar levels, but no standardised achievement tests for drawing square circles. Presumably you could develop one, but since everyone would fail, what's the point?

That said, I don't think that standardised aptitude testing necessarily evokes a '“latent trait” that is univariate, homogeneous.' For example, if I understand the history of IQ testing right, it was originally designed to measure a variety of factors that contributed to school success. I understand the airforce tests mental ability and eyesight in standardised aptitude tests for its would-be pilots. Indeed, eyesightness itself is neither univariate nor homogenous.

Well, we're getting a bit technical here, but it's a fundamental point. Standardized ACHIEVEMENT tests do AIM to measure achievement, but the Item Response Theory that undergirds their construction doesn't measure that. It measures a latent trait masquerading as achievement. You don't have to take my word for that. "Look it up" in the first few paragraphs of an account of IRT: http://edres.org/irt/baker/chapter1.pdf

Driving tests, blood sugar tests, and eye sight tests are all direct measures and in no way rely on Item Response theory that is the essential foundation of standardized achievement tests.

The Binet test WAS invented to identify kids on France requiring "special education." It was an ordered series of tasks exactly of the same nature as I sketched for reading. It had no "quotient" abstract scale. The diversion of the original invention and intention has had a very deleterious effect that is still very much with us.

The aptitude-achievement test distinction: a study of unrelated children reared together, Behavior Genetics, 7, 465-470, 1997. (Unrelated children reared together (N = 156) in 71 different families included in the Texas Adoption Project were compared for similarities on intelligence and achievement tests. The purpose was to see if a distinction between the two types of tests based on their heritabilities could be sustained. Results indicated no substantial differences in correlations for the two types of tests, and hence little or no support for the notion of an aptitude-achievement distinction based on differential heritabilities.)

I don't see the relevance of this study to the thread, Ken. The study focused on differential "heritablities." If the instelligence tests and achievement tests were the conventional paper/pencil, multiple choice, they were constructed per Item Response Theory that I've been referencing, but the genetic considerations of "heritability" are a whole nother story.

The terms "intelligence/mental ability," "aptitude," "ability," and "achievement" are tossed around very carelessly. For example, the SAT was born as the "Scholastic Aptitude Test" and was thought to measure something that "couldn't be taught." Now it's just an acronym for "whatever the test measures."

My contention is that school achievement can be measured transparently and that it's possible to do so in a psychometrically sound way using available methodology.

Dick, that study actual agrees with your contention. Achievement tests, usually a product of IRT, are the same as IQ tests. I believe the point about heritability was just a round about way of saying that environmental factors has the same effect on achievement test performance as they did on IQ tes performance.

Dick,

What are some tests that you think are "psychometrically sound"?

I am just curious.

jh

Well,There are thousands of "psychometically sound" tests listed in the Mental Measurements Yearbook.

It's the "direct,transparent" aspect of measuring school achievement that's the concern. Conventional standardized achievement tests are "psychometrically sound." It's just that they're not sensitive measures of what teachers are teaching and what kids are learning.

I've been trying to explain why that is and to sketch an alternative orientation that can provide a means for schools to reliably accomplish the aspiration of NCLB and that will yield useful info about the accomplishments of teachers, schools, LEAs, aggregated by the biosocial indicators of interest.

As as has been pointed out in this thread, if you want a gross basis for ranking or predicting, the standardized achievement tests are fine. But you'll do equally well with a 10-minute vocabulary test.

Dick,

I checked out your reference. There are tons of tests, and it wasn't clear what you're getting at.

Can you please provide a concrete example as to what you object to and what you'd like to see?

For example, you could give sample questions (you can make one up) for what you see and what you'd like to see.

thanks

jh

Standardized ACHIEVEMENT tests do AIM to measure achievement, but the Item Response Theory that undergirds their construction doesn't measure that. It measures a latent trait masquerading as achievement.

Ah, a different definition of latent trait than thought you were referring to.

Next question - what do you mean when you say "a latent trait maquerading as achievement"?

I also, in your reference, don't see anything that states that an Item Response test posits a The theory and practice of standardized achievement testing posits a '“latent trait” that is univariate, homogeneous'. They do say that performance varies from examinee to examinee, but that's not surprising. Everything that humans can do we can do with varying ability.

Driving tests, blood sugar tests, and eye sight tests are all direct measures and in no way rely on Item Response theory that is the essential foundation of standardized achievement tests.

So driving tests, blood sugar tests, and eyesight tests aren't standardised achievement tests? So when the guy conducting your driving test asks you to do a 3-point turn, and then asks you to do a hill start, he's not using Item Response theory?

It appears that we are using words in very different ways and I would like to understand what you are talking about.

Yes, Tracy and I ARE using "standard(ized)" tests in different ways. The "paper-pencil-fiil-the-bubble-report-an-ungrounded-number" tests that aremandated by NCLB and that serve as the common basis for dealing with "achievement" in educational research and practice is what I'm referring to.

These tests go back to the days when psychologists viewed the "mind" as comprised of "traits" or "factors," which because they existed in some amount, could be measured. The statistical analysis of the measures would yield a mental map. To make the analysis honest, each trait had to be univariate and homogeneous.

That quest was long ago abandoned, but the theory and practice slopped over into measuring school achievement--not only slopped over, but took over the endeavor.

Before the 1960's the major publishers of standardized achievement tests (there were only 3 and they were very tiny) were careful to warn users that the tests were NOT to be used to measure the acccomplishments of individual students or teachers. They could be used by administrators to identify schools that could use additional attention and support. Teachers seldom saw the results; students never; and newspapers, never, never.

That changed when the fed and state governments began to get more prominently in the act. They legitimately wanted to know "what the public is getting for the expenditure."

The testing industry didn't change either their theory or their practice of test construction. They made it more mathematical,so that even the simplified explanation I cited is something that few people today are willing and able to wade through.

The industry also permitted and encouraged sloppy language to cover up the deficiencies of the tests. So today we have the ludicrous situation of treating an arbitrarily-set cut score on a forced-normal distribution as "proficiency."

No one even blinks or winks. The best you can get is, "Yes, standardized tests do have their limitations, but they're the best we have." And the beat goes on.

Driving tests, blood sugar tests, and such ARE "standard" measures. The term "standard" has positive connotations and those were picked up when the term "standardization" was applied to the norming process: standardized=normed, nothing more or less.

The results of driving tests, blood sugar tests, spoonfuls and all the other measures that fill our lives aren't reported in terms of relative numbers of those ranking above and below the mark. They're not composed of "items" that are "secret." Only in education--where kids' futures are at stake.

I stumbled across a review of a new book that is relevant to what we've been talking about: "Measuring Up: What Educational Testing Really Tells Us" by Daniel Koretz of Harvard.

www.educationsector.org/analysis/analysis_show.htm?doc_id=692268

If you want to rub your nose in psychometric detail, you'll find confirmation of what I've been briefly trying to say about standardized achievement tests:

"With such an emphasis on the complexity and limitations of standardized testing, it is no surprise that Koretz strongly condemns NCLB's test-based accountability system."

However:

"But, while he clearly describes the limitations of testing, he doesn’t suggest how to create the effective accountability system he desires. The book literally ends with his advice to 'Let the buyer beware.'"

Caveat emptor is a cop out. There is no "buyer" choice in the matter. The government mandated tests have already been "bought" and simple, unobtrusive alternatives are not on the table.

The beat goes on.

"To make the analysis honest, each trait had to be univariate and homogeneous."

Why is it impossible to be honest if the trait is multivariate and/or hetrogeneous? I suspect a mathematical proof might be useful here. And what do you mean by honest in this context?

And what do you mean when you say "a latent trait maquerading as achievement"?

Before the 1960's the major publishers of standardized achievement tests (there were only 3 and they were very tiny) were careful to warn users that the tests were NOT to be used to measure the acccomplishments of individual students or teachers.

Coming from a non-US educational system, where exams have been used long before the 1960s to measure the accomplishments of individual students (Bursary, School Certificate, etc), I'm not sure of the relevance of this statement. How were the achievements of individual students in the USA measured before the 1960s? Was this better or worse than the results achieved by standardised achivement tests?

So today we have the ludicrous situation of treating an arbitrarily-set cut score on a forced-normal distribution as "proficiency."

Okay, I'm lost. The more I ask you, the more confused I get. We have gone from standardised achievement tests to tests based on Item Response Theory (and I still don't know if you think that driving tests are based on Item Response Theory or not) to "paper-pencil-fill-the-bubble-report-an-ungrounded-number" tests". And now you appear to be talking about not merely fill-the-bubble-report-an-ungrounded-number, but also tests that have arbitrarily-set cut scores and forced-normal distributions. Are the criticisms you originally stated intended to apply to all standardised achievement tests or only to ones that are "paper-pencil-fill-the-bubble-report-an-ungrounded-number" with arbitrarily-set cut scores on forced normal distributions?

It sounds to me like you are saying some very important things, but without a clear definition of what you mean by "standardised achievement tests" I don't think I can figure out what sorts of tests your criticisms apply to.

Personally to me the worrying thing about the reading tests is how difficult it is to find out information on the validation of any test, but validating tests, and making the validation information widely available, is a fixable problem, while you appear to be arguing that the problems with standardised achievement tests are unfixable.

Sorry I've confused you. But all standardized achievement tests are constructed per Item Response Theory and none are "fixable." They all inherently have the fatal flaws I've described.

Okay, let's design a standardised achievement test for reading using criterion tests rather than norm-based and reasonably non-arbitrary cutoffs. We will assume that money and time are no object.

To start, let's decide our goal. I suggest that an objective of schools should be churning out kids who can read and comprehend a newspaper. Pick the newspaper, this should vary based on country. Break down "read and comprehend a newspaper. Write down a set of tasks that a kid who can comprehend the newspaper should be able to do - eg find in the classifieds a flat for rent costing between $200 and $300 a week, be able to answer the who, what, when, where, why of the lead story, be able to summarise the main argument of the editorial.

Gather a bunch of people with different levels of reading ability, some of whom can comprehend a newspaper, some of whom can't comprehend a "Danger" sign, some in between. Order them in terms of qualitative performance on the "comprehend a newspaper" subtasks. Develop, using Item Response Theory, test items that distinguish between those who have no ability to read a newspaper and those who can read Shakespeare. Determine a cut-off score based on the relative importance of Type I versus Type II errors. This is a subjective judgment, for example if you are developing a standardised achievement test on "safe handling of explosives" your cut-off score should be set very high to reduce the chance of passing someone who doesn't know much about safe handling of explosives but happened to get lucky on some test responses, at the cost of failing some people who know a lot about safe handling of explosives but happened to have bad luck on some test responses - so you favour Type II errors over Type I errors. When it comes to general reading comprehension, the costs of a false positive are lower than in the explosives example, so the cut-off score doesn't need to be as tight.

Check test validity on a second group of people with different levels of reading ability (I'm inclined to call this out-of-sample testing). See if those who perform high on the test are better qualitatively at comprehending a newspaper than those who do badly. For extra validation, see if those who perform well on the test do well at reading comprehension tasks outside newspapers. Make refinements and re-validate on new out-of-sample groups as necessary.

It may be necessary to develop different tests for different ages, eg young children are not particularly good at sitting still from a long time.

This should result in a test designed using Item Response Theory that discriminates between students based on their ability to read and comprehend a newspaper. Despite reading being a multivariate, hetrogeneous skill.

Well, you're getting closer. But we can apply Occam's razor and drop all the IRT ceremony. The intent is to determine if a kid "can read" not to compare kids on a scale.

And we can do some other "tidying up."

A "newspaper" is a particular genre that requires some background information. The sports section, the entertainment section, the world news section, the classified ads, the business section and so on each requires specialized information. This information goes beyond "reading" and is illustrative of the "contaminants" that account for the correlation with SES.

The easiest way to avoid this "contamination" is to construct text passages using a vocabulary that aggregate children will have within their spoken lexicon. That gives you several thousand words to play with. The lexicon can reflect the range of syntax and other grammatical features of English and the common genres, including "news," other non-fiction and fiction.

You can construct as many "parallel forms" of the test as you like. It won't take many to determine if a kid can read. And there are other templates, such as nonsense words that can also be used. The number of kids who can read can be tallied and arrayed by the "usual" demographic and biosocial categories of interest.

The focus then shifts to the kids who "can't read." But that's an instructional, not a measurement matter. The concern here is with programs that reliably deliver kids who will be able to "pass the test" per the above. The DI product/protocols are one alternative. There are others, but they're not in common use in the US. You have to go to the UK to find them.

With this orientation, programs can be empirically compared using standard reliability of effect, time, and cost criteria. And programs can be "upgraded" with experience.

In short, it's quite feasible to "get a handle" on instruction that is currently "out of control" and running on rhetoric.

There are others, but they're not in common use in the US. You have to go to the UK to find them.

Dick (and the rest of you RRF readers), which programs are these and is there any research?

The Brits use the term, "Synthetic Phonics" for the programs. (Their history of reading instruction parallels but is a bit different from US experience, and it's "programme" in BritTalk.)

The most popular instructional architecture was pioneered by Jolly Phonics. There is one study, known as the "Clackmannanshire Study" that provides evidence of effectiveness and many, many anecdotal reports of "amazing results."

The Brits report results in terms of reading or spelling "age", so they have the same ungrounded info that the US has.

There are several knockoffs of this architecture, including a detailed outline for a program constructed under the auspices of the UK government, "Letters and Sounds."

www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/local/clld/las.html

Another architecture follows the kind of scripting that characterizes DI. There are a couple of such, and again anecdotal reports of "amazing results." Example:

www.prometheantrust.org/index.html

A third architecture is a variation of phono-graphix called Sounds~Write. They have several years of data in terms of "spelling ages."

Two additional architectures are recent entries:

"International Phonics" is an online program constructed by Debbie Hepplewhite, President of the RRF:

www.phonicsinternational.com/

guidance_book.pdf

BRI-ARI was developed in conjunction with R&D that I've been involved with over the years. It is supported by voluminous research. The link below barely scratches the surface of the "lit" but will likely suffice:

/www.piperbooks.co.uk/technical_papers.htm

Those are the five architectures, as I view the scene, but others may view it differently. The links I've given are not meant to promote the programs, but simply to provide quick entry for anyone caring to look into the matter further.

While we're talking "across the Atlantic," it's worth mentioning that France has also officially abandoned Whole Language (method globale) and adopted "La phonique synthétique." The program Leo et Lea (play on the verb "to read" lire) is a hybrid of Jolly Phonics and BRI architecture.

www.leolea.org/

The politics involved in overriding the dominance of Whole Language instruction in both the UK and France are complex, but they are each further along, in my view, than the US, where WL masquerades as "Balanced Literacy."

Oooops. I forgot to paste in the link to the Sounds~Write site

www.sounds-write.co.uk/downloads.asp

Note that this site and also the International Phonics site have very useful arrays of the full English Alphabetic Code. The structure and substance of the Alphabetic Code have been widely overlooked in the US, where the Code is commonly misrepresented as a "principle."

The characteristic that all the architectures share is that the Alphabetic Code, which provides the link between written and spoken language, is foundational to reading and spelling instruction.

A "newspaper" is a particular genre that requires some background information. ...

The easiest way to avoid this "contamination" is to construct text passages using a vocabulary that aggregate children will have within their spoken lexicon.

However, it strikes me that given the goals of education, the most effective way is to "contaminate" low-SES kids with the knowledge of how to read a newspaper, eg what the entertainment section is, what an editorial is, etc. I went to a low-SES school for pimary school. We did have some sessions on how to read a newspaper when I was ten. The easiest way is not always the best way.

Of course this discussion assumes that schools should be churning out students that can read newspapers, if a different goal is picked then that should affect teaching.

IRT theory is important because it is a guide to constructing tests that can make fine distinctions between different skills levels. This may not always be relevant - for example when dealing with high explosives you want to get *everything* right. But a kid who can't read a newspaper but can read a DANGER sign is better off than a kid who can't read at all, so the discrimination provided by IRT is important.

I am still curious as to what you meant when you said "a latent trait masquerading as achievement". Can you please explain this comment?

The thing is, IRT, doesn't make "make fine distinctions between different skills levels." It makes fine distinctions on a scale that has been forced into a normal distribution and given a skill label.

For example, it doesn't tell you if a kid can read two syllable words like "danger"; whether the kid has learned to handle the alternative letter/sound correspondences for vowels and hard and soft /g/. And so on. All the IRT test gives you is a scaled number.

The IRT grinder spits out "items." The items are selected so that each item maximally measures what the other items in the test are measuring. That "what" constitutes the "latent trait." With respect to IRT achievement tests, the "what" is NOT what a teacher has taught.

The IRT tests, however labled, are not sensitive to instruction. Sure, you can get statistically significant differences between, say DI and a control group. And you can nudge the scaled mean up a bit in the aggregate and proclaim "gains." But if a skill has been taught, and you measure the learning, you don't get a normal distribution. You get a skewed distribution with the great bulk of scores piling up at the top. And you'll never get such results with an IRT generated test.

IRT inherently precludes instructionally sensitive measures. It keeps changing the item content from grade to grade to maintain the integrity of the scale.

What the IRT acchievement tests ARE sensitive to is SES. The "achievement gap" of poor kids will NEVER be eliminated if IRT generated tests are the metric. DI and the other programs I've cited can reduce the correlation between SES and reading achievement to near zero. But the measure of achievement has to be be transparent and operational, not artificial and attributed. The point I've been trying to make here is that methodology for such measures and practice is readily available.

Thanks for the links, Dick.

I would think that even with a well-designed criterion test, there will still be a distribution of scores that approximates a normal distribution, unless the students do so well or poorly to get bunched up at the minimum or maximum.

Not that this changes anything with the problems with the IRT tests.

While I'm no pyschometrician, I'm sure there must be some ways that test makers can assure that questions on criterion tests are valid and reliable.

The only time one gets a "normal" distribution is when the determinants of the phenomenon are multiple and complex and are not subjected to control. This is NOT the situation with instruction--at least it's not the intention. The whole purpose of instruction is to reliably deliver an aspired accomplishment--such as to teach all kids to read. To make this happen, all would pile up at the top. The situation would be "normal," but the distribution wouldn't fit the normal distribution.

There are a couple of very severe limitations of thinking in terms of "criteria." One is that the specified statements don't "add up"--they're duplicative and they overlap. This holds for the alleged "5 essentials of reading" for example. The other limitation is that the statements are wishful and are not coupled with the means for obtaining transparent accomplishments. This holds for the entire "standards movement."

Actually. when it comes to measuring achievement, the LESS you know about psychometrics the better off you are. The field is steeped in IRT and comparative statistics; both liabilities rather than assets. And the psychometric jewels of reliability and validity are devoid of utility.

In measuring achievement transparently you can replicate the measurement easily in a few minutes to confirm that you have a reliable indicator of current status. And you can get validity via transparent observation of what has been taught. None of what's involved entails any fancy psychometrics.

The complications arise in instruction--not measurement. Developing product/protocols for instruction that reliably yield specified aspired accomplishments is straightforward but not simple.

Prevailing thinking (DI'ers and RRF'ers excepted) is: "Programs are unimportant. Qualified teachers are the route to improvement." This belief serves the interests of both colleges/universities and collective teachers. But it doesn't serve the interests of individual teachers and of collective students.

"Qualified teachers" are apple pie in the sky. The question is what we can do with the kids and teachers we've got now. There's adequate potential, but the prevailing beliefs of the people at the top are currently misguided and very resistant to change.

"Leadership building" to effect belief change at the elite level can happen. It's usually not initiated by the elite, but that's a whole nother story.

IRT inherently precludes instructionally sensitive measures. It keeps changing the item content from grade to grade to maintain the integrity of the scale.

No it doesn't. The questions only change from grade to grade if someone actively rewrites the items. If you use IRT once and then don't rewrite then items will remain the same. That's why I specified that we'd develop the IRT using a sample that we know varies in reading ability.

If we then apply this IRT-generated test to a population that has been taught to read, if we have validated the test right, and if we don't rewrite the item content when we apply it to a general population, I don't know why you think we will still get a normal distribution.

ut if a skill has been taught, and you measure the learning, you don't get a normal distribution. You get a skewed distribution with the great bulk of scores piling up at the top. And you'll never get such results with an IRT generated test.

So, if I call up Mensa, round up some recruits who are known to perform really highly on IQ tests, and give them an IRT-generated IQ test that was generated based on a full range of the population, I will somehow get a normal distribution?

All the IRT test gives you is a scaled number.

And if what you want to do is monitor the performance of a school or of a curriculum, or of a country as a whole, what you want is one scaled number. It's important for a teacher to know if an individual kid in the class can read two syllable words like "danger", it's important for the principal to know that for individual kids, but it's impossible to know that for thousands, let alone millions of kids.

There's a difference between data and information. There's a point in which you have so much data that you don't have any information. At this point, throwing away data (in an intelligent way) is the way to generate information. For policy purposes, it's important to know things like "Programme B moves 95% of kids to the level where they can at least read a newspaper while Programme A only moves 82% of kids to that level."

Just to repeat myself, I agree that it is very important for teachers to know the details about their individual students' performance.

"Programme B moves 95% of kids to the level where they can at least read a newspaper while Programme A only moves 82% of kids to that level."

Precisely! That's exactly the sort of measurement (with the caveats I've mentioned for the newspaper genre) I've been advocating. But IRT is not relevant to generating such information. Rather, it's counter-productive.

The example re Mensa is a red herring. If you preselect a sample formed by high scores on an IRT test, you'll get a distribution piling up after the cut score and then skewing to the upper tail.

The substance of reading and math IRT tests at grade 3 and 8 is certainly different. That's all I've been trying to convey in saying that the tests are ungrounded. The definition of what constitutes "reading" is different at the two grade levels. But reading and math expertise is not a question of age; it's a question of instruction and performance. The instruction occurs over time, and there are sensitive time periods for differing instruction, but beyond that age/grade is not a relevant measurement consideration.

But IRT is not relevant to generating such information. Rather, it's counter-productive.

This is something about your arguments that I don't get. How is IRT irrelevant? Isn't it better to have a test that can discrimate between a kid who can read a newspaper, a kid who can read a "Danger" sign, and a kid who can't read at all?

The example re Mensa is a red herring. If you preselect a sample formed by high scores on an IRT test, you'll get a distribution piling up after the cut score and then skewing to the upper tail.

Hold on. You were claiming in your earlier comment that "You get a skewed distribution with the great bulk of scores piling up at the top. And you'll never get such results with an IRT generated test."

I have now given you an example of a case in which an IRT generated test produces a skewed distribution with the great bulk of scores piling up at the top. This is exactly what you said can't happen. And then you dismiss this as a red herring. What's going on here? Either IRT-generated tests can sometimes produce skewed distributions or they can't.

The point I am trying to make is that if you develop a standardised achievement test using IRT on a population with different reading abilities, what you wind up with is a standardised achievement test that will recognise improvements in the total student population. The only way that IRT inevitably leads to a normal distribution regardless of teaching is if you re-design the item content every time you change test populations. It is perfectly possible to design a standardised achievement test and then not re-norm it every time you change test populations. Indeed, once you've validated the test in the first place, it's easier than continually re-norming it.

I was going to ask if the IRT applies to the standards-based tests, most of the state tests for NCLB are of this type. I found a list once at the ed.gov website and it listed all the state tests and whether they were standards-based or norms-based. About three quarters were standards-based. My district uses some normed tests too, but not for NCLB. These essay-type tests seem to have a lot of the characteristics Dick Shutz approves of. Ours have no true/false, multiple choice or short-answer type questions, they are all essays or problem-solving (explaining is the part that counts), and are called "constructed-response" tests.

They are closely matched to what we actually teach, so I guess that is grounded. An example, the question is different every year, but every year we know that the children will have to write a persuasive letter on a topic related to school -- something like a longer lunch hour, or extra recess, or school rules, or uniforms, or using calculators, or internet blocking software -- some issue where they can have an opinion and give reasons to support it.

In the curriculum for third grade we are supposed to teach kidsto write a persuasive letter, so by doing what we are supposed to do, we prepare the kids for the test. The exact items change every year, but they follow the curriculum very closely. There are no tricks. It is possible for every child to do well enough to meet the minimum standard. Of course, we always have kids that are new, or who are ELL, or do not have the needed skills yet, but in fact most of our kids do quite well. The scores pile up -- not at the absolute top, but at the upper middle. So I guess that means its a good test? It seems to be testing what we actually teach or are supposed to be teaching. The school has a strong primary team.

The tests are graded by college students and others using a rubric. There are no right and wrong answers. They told us how they check to make sure grading is consistent: random double grading, and training for graders, and questionnaires to schools asking if they see "anomalies" . Once in a while we see mistakes on the test -- inclusion of things that aren't in our grade curriculum, but I am told that those errors are caught in the grading process and not counted towards the children's final scores which are all rubric levels, not numbers.

I don't see how item response theory works here, if it does? Maybe it doesn't. The other puzzling thing is that there is not a lot of consistency between the state tests and the normed tests the district uses. We do see more of a bell curve on that, but with the state test is is "piled near the top" . I like that way to describe it.

First Tracy:

"How is IRT irrelevant? Isn't it better to have a test that can discrimate between a kid who can read a newspaper, a kid who can read a "Danger" sign, and a kid who can't read at all?"

Of course. But IRT tests don't report the results in this way. To determine if kid can read a newspaper, have kid read a newspaper (with the caveats I've mentioned.) To determine if a kid can read Danger sign, have kid read the sign--but because kid can read that sign doesn't tell you what else kid can or cannot read. And it's easy to tell if a kid can't read anything. Kid can't read anything. At any rate, in none of these instances is IRT relevant.

Back to Mensa. You didn't FORM a distribution that was non-normally distributed. General mental ability IS normally distributed. The Mensa sample represents the top end of this distribution. You just chopped off the top tail.

You've got the matter of IRT in test CONSTRUCTION and test NORMING all tangled up. IRT per se stops with test construction. Scaling/norming/standardizing the test is a separate matter. IRT facilitates the norming by forcing the scores into a normal distribution. One of the alleged strengths of IRT is that it yields "pure" measures of the latent trait involved--independent of population characteristics.

The flaw is not in the theory; it's is the application of the theory to academic achievement--which is not a latent trait and does not meet the requirements of the theory.

Moving on to Teach3rd's questions re "standards based tests"

If an achievement test is constructed constructed via IRT, the scores will be forced into a normal distribution reflecting the latent trait, irrespective of whether the items appear to reflect aspects of standards. Many standardized tests provide concordances to show how the same test is applicable to the standards of every and all states. Even when the test content is tailored to the standards of a given state, the sampling of the standards is per the IRT and the nasty little distractors are there to get at the latent trait rather than the achievement.

Yes, the writing/composition test as you describe it is an example to the transparent measure of achievement that I've been touting. To determine if kids can write a persuasive letter, have them write one.

The fact that the tests pile up at the top indicates good instruction.

But if you test what teachers have taught, those are the results you'll get.

The fact that the state tests correlate with the results of this test (which is what I understood you to say) derives from the fact that the IRT generated tests do tap general ability. A very brief vocabulary test would have virtually the same correlational pattern. But if your composition scores are piling up at the top, you've knocked out the correlation with SES--the matter that Ken launched the thread with.

Composition is a different matter than reading and math and each school subject raises its unique measurement issues. But the issues also overlap. For example, there's the overlap of spelling and punctuation. Familiarity with a given genre in reading will aid and abet composing the composition, but the composition act brings additional complexity.

These instructional relationships and contingencies are seldom analyzed, let alone sequenced. Neither standards statements nor standardized tests illuminate the contingencies. All it takes is a thinking cap and a little bit of thinking about the sequencing goes a long way. But when all eyes are focused on "making AYP," not much thinking gets done.

It takes a lot more work to simplify any matter than it does to make it it more abstract and complex. El-hi measurement over several generations has generated sloppy and confusing language that is often deceptive. And it's operations are so mathematicized (if that's not a word, it is now) that few have any notion of what's going on. When this happens in other sectors of life, it's not tolerated or is labeled shamanism--unrelated to the reality of the situation. More thinking is needed.

In Maryland the test scores for schools are reported in three categories that equate to does not meet, meets, and exceeds. If you set the meets and exceeds bar low enough, the scores will pile up at the top.

When it comes to testing reading, how does reading a passage tell you when a student "can read"? Do they need to read 100% correct or is 98% okay? Shouldn't the reading test have several passages of varying difficulty and then comprehension questions about each passage that are also of varying difficulty? This would tell you how well the kids can read.

Whether you end up with a normal distribution would really depend on the floor and ceiling of the test. If the ceiling on the test is grade level performance then the scores should pile up near the top. So the test could tell you that third graders can read at a third grade level, but it would never find the third grader who can read at sixth grade level or a seventh grade level because it is off the scale. It is sort of like the speedometer that only goes to 80. Once you go over 80 all you can say is you were going fast.

My oh my. Reading expertise is not in terms of grade levels. That's an artifact of standardized testing. If a person can handle the Alphabetic Cod and the othr linguistic conventions involved in the written English language, the individual "can read." We've been talking about the measurement means for determining that.

Md and other states ar setting arbitrary cut scores and on ungrounded tests declaring them as defining differential reading expertise. It makes no sense whatsoever.

Dick,

Thanks for all the energy you are putting into this conversation.

One nitpick:

I think you are making a faulty assumption. Low SES students do not have very large vocabularies.

The test you propose for determining whether children can read phonetically would likely cause some low SES students to fail because of their limited oral language vocabulary.

A nonsense words test might be a better choice.

Of course. But IRT tests don't report the results in this way. To determine if kid can read a newspaper, have kid read a newspaper (with the caveats I've mentioned.) To determine if a kid can read Danger sign, have kid read the sign--but because kid can read that sign doesn't tell you what else kid can or cannot read.

IRT tests could report the results in that way. The reason for developing a standardised achievement test is to get a measurement instrument that is reasonably reliable regardless of where the test is being administrated and who is administrating it.

One of the important things for doing good research is to remove the subjectivity from the results of the experiment. In physics, there was a case starting in 1903 when a physicist (René-Prosper Blondlot) thought he had discovered a novel form of radiation, called N-rays, as a result of changes in the brightness of an electric spark in a spark gap placed in an X-ray beam. Eventually another physicist, Robert W. Wood, proved that the scientists who were observing the N-ray effect because the scientists still reported that they saw N-rays after he had secretly removed an essential prism from the experimental apparatus.

There are a number of proven cases of school administrators and even individual teachers blatantly cheating on tests (as in filling in the wrong numbers). If the only way we tested reading ability was to ask kids to read a newspaper, or a danger sign, then the opportunities for not merely blatant cheating but unconscious bias, as what was happening in the N-ray case, are endless. If you are to do proper research on reading instruction, you need a standardised achievement test. (You also need a lot of other things, but I'm already in the habit of writing overly-long comments).

. You didn't FORM a distribution that was non-normally distributed. General mental ability IS normally distributed. The Mensa sample represents the top end of this distribution. You just chopped off the top tail.

Yes, that's the point. The reason I did this was because you were claiming that "You get a skewed distribution with the great bulk of scores piling up at the top. And you'll never get such results with an IRT generated test." The reason I presented a hypothetical argument was in response to the argument you had made.

Now, let's develop, using IRT, a test that distinguishes between different levels of reading ability, from not being able to read at all, to being able to read Shakespeare. Without re-writing the test, we then administer this test to children who have all been taught to read. We are going to get a skewed distribution out the other end. Do you agree or deny?

You've got the matter of IRT in test CONSTRUCTION and test NORMING all tangled up. IRT per se stops with test construction. Scaling/norming/standardizing the test is a separate matter.

Dick, you are the one who said that "IRT ...keeps changing the item content from grade to grade to maintain the integrity of the scale.". I am the one that has been firmly telling you that IRT is a separate matter from scaling/norming/standardising. I have never gotten the two tangled up.

I make plenty of mistakes of my own, please don't accuse me of errors I have never made.

The flaw is not in the theory; it's is the application of the theory to academic achievement--which is not a latent trait and does not meet the requirements of the theory.

To quote from the reference you provided, at http://edres.org/irt/baker/chapter1.pdf:

"In academic areas, one can use descriptive terms such as reading ability and arithmetic ability. Each of these is what psychometricians refer to as an unobservable, or latent, trait. Although such a variable is easily described, and knowledgeable persons can list its attributes, it cannot be measured directly as can height or weight, for example, since the variable is a concept rather than a physical dimension."

Now when you first started talking about latent traits, I thought you were referring to the ability to learn to read, as oppposed to measuring reading ability, or literacy directly (eg, most humans are capable of learning to read, but if we are not taught to read, most of us remain illiterate). But then, once you corrected me, I understood that by "latent trait" you were referring to a trait that cannot be measured directly, unlike height or weight.

Now I agree that literacy cannot be measured directly. We can measure manifestations - can you read this passage? But we can't measure literacy like we can measure weight. So by this definition literacy is a latent trait.

Now, however, you are claiming that literacy is not a latent trait. What gives? Either literacy is a latent trait by your definition or it isn't. You can't have it both ways.

(And while we are at it, regardless of whether literacy, or reading achievement, is a latent trait or not, IRT can be used to design tests to meausre it).

I was going to ask if the IRT applies to the standards-based tests, most of the state tests for NCLB are of this type.

Item-Response Theory is a way of designing a test that discriminates between different levels of a trait when you can't measure the trait directly. Nothing more, nothing less. It can be used to design standards-based tests.

If you are using IRT to design a standards-based test then showing the validity of the test is more of a problem than if you are using IRT to design a norm-referenced test. On the other hand, showing test validity for a standards-based test is a problem regardless of whether or not you are using IRT.

IRT is often used to force scores into a normal distribution, but it could be equally well used to force scores into any probability distribution you like - uniform, barbell, etc.

Clarification for Ken re vocabulary.

You're right. Low SES kids do tend to have limited vocabulary. This works against them in standardized reading tests, many of which deliberately manipulate vocabulary to spread kids out on the measure.

However. All aggregate kids entering kindergarten have at least 3000 words in their spoken vocabulary. The lexicon was derived empirically by determining that kids could all understand the terms. The resulting lists have been compiled. The lexicon provides an ample basis for tapping all the complexities of written English grammar. I'm proposing to use this lexicon as a basis for composing the texts to determine if kids can read. If a kid couldn't understand a communication in spoken language it doesn't make sense to view lack of understanding of the communication in written to be a "reading problem." It's this kind of bias that leads to the correlation between standardized tests and SES.

Tracy, the kind of things you contend IRT tests "could do" would violate the theory, and the analogies outside of instruction are inapt.

You're right. The author of the paper on IRT describes the theory.

IRT theorists DO treat academic achievement as a latent trait. But with a quick slight of hand, they don't use the term. Talking about "latent traits" they'd be laughed off the floor. They use the term "ability." But it's word magic, in the same vein as re-labeling a cut score as "proficiency."